ACT III – The Legacy of the Polish School and the 1970s/80s

This article is the third in a series on the history of theater posters in France. It traces the origin of theater posters and their specific characteristics, reflecting our society’s evolution from pure text to image, through typographic creation and digital media.

Complete series

Preamble : The history of theater posters in 6 acts

ACT I – The golden age of the poster in the 19th century

ACT II – The Glorious Thirty of theater posters 1950/60

ACT III – The legacy of the Polish school and the 70/80s

ACT IV – The Posters of the Théâtre de la Colline, from Batory to the ter Bekke & Behage Studio

ACT V – The intrusion of Contemporary Art

ACT VI – The decade of social networks + the typographic reign

The Cold War was already well established when, in 1961, Berlin woke up divided in two by a wall. The Algerian War was not yet over, and the government at the time was calling up many conscripts. To escape the military uniform, Michel Quarez, a young graduate of the École des Arts Décoratifs, went to Warsaw for a year to study posters. He would be the first Frenchman to join Henryk Tomaszewski’s workshop. “Tomaszewski was a legend in Europe, even though in France, no one talked about him in art schools,” Michel Quarez would later confess.

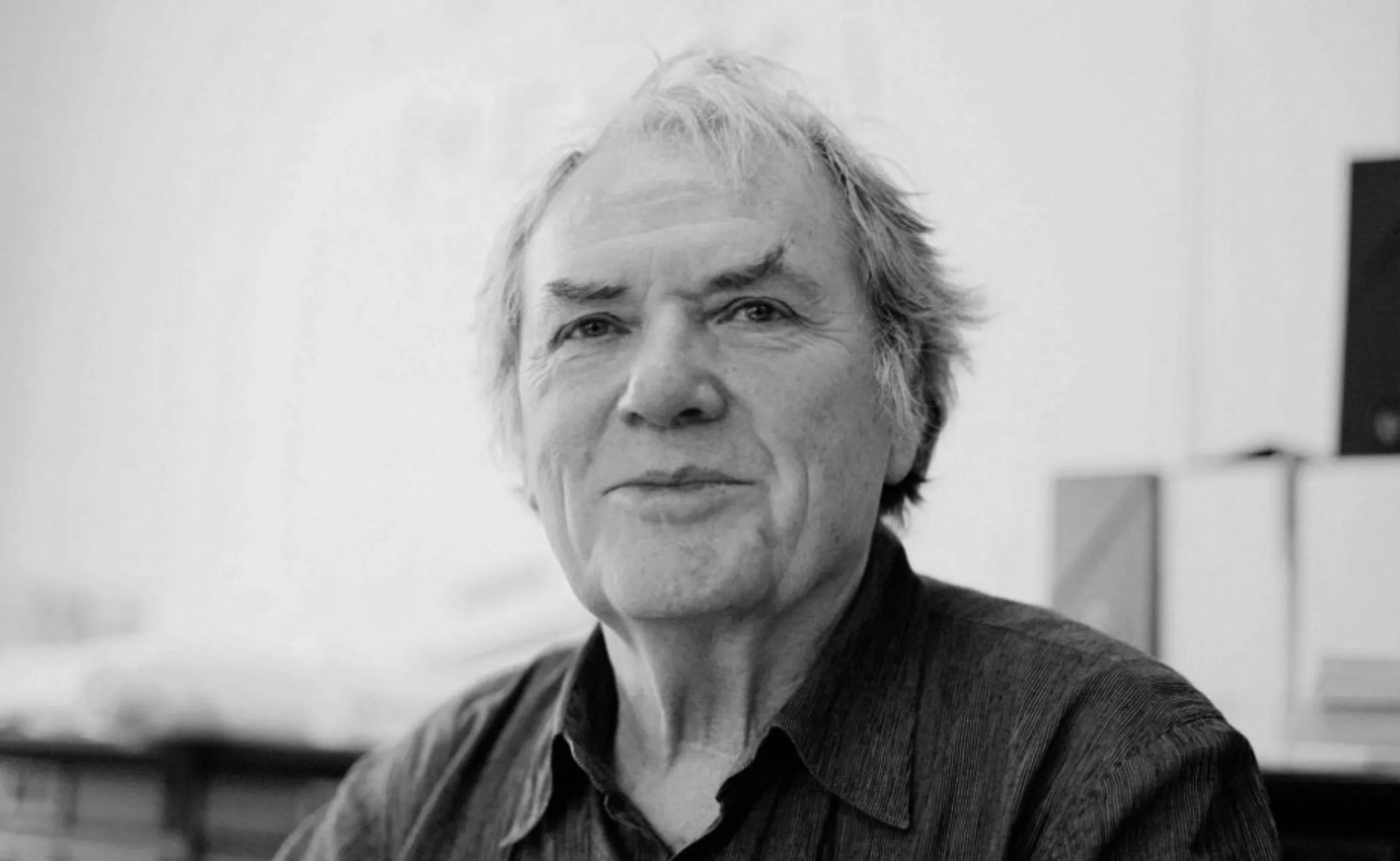

The Polish school, posters with double meanings

What came to be called the “Polish School of Poster Art,” to borrow the words of one of its most famous graphic designers, Jan Lenica, was a generation of creators who had a decisive influence on many graphic artists worldwide. In 1950s Poland, the poster was one of the few artistic expression spaces tolerated by the Communist state. The state controlled cinema—the ultimate propaganda tool, or rather “a means of social education and cultural dissemination”—as well as theater, visual arts, and music.

The Polish artists knew how to appropriate this medium to demonstrate exceptional freedom despite constraints and lack of budget, conveying double-meaning messages to evade the omnipresent censorship, hallmarks of the productions from that era. Paradoxically, the limited technical resources at their disposal multiplied their creativity. There was neither competition nor advertising; everything was nationalized.

Upon his return to France, Michel Quarez organized an exhibition that attracted the attention of many students, including Pierre Bernard and Gérard-Paris Clavel (the future co-founders of the Grapus collective), who were captivated by the quality of the posters they discovered. They too would join the Warsaw workshop a few years later. Then it was the turn of Alain Le Quernec and Thierry Sarfis to “make the journey East.” It was an entire generation that would thus create posters in the tradition, rigor, and effectiveness of Tomaszewski’s teaching. Their signature approach became the reduction of a play’s theme to a visual metaphor, where the juxtaposition of two elements crystallizes a personalized poetic evocation.

“Run, comrade, run, the old world is behind you!!!” Soon, May 1968 would ignite a firestorm with an explosion of posters produced by the Popular Workshop of the Paris Beaux-Arts and the Decorative Arts Workshop. Every day, new screen-printed posters flooded the walls of the capital. Political engagement found in paper a reason for existence. A new graphic language was born.

Grapus

In the early 1970s, after their involvement in creating the May ’68 posters at the Arts Décoratifs and their training at the Institute of the Environment, Pierre Bernard, Gérard Paris-Clavel, and François Miehe founded the Grapus collective, which would revolutionize graphic design in France for two decades. We mentioned them in this article.

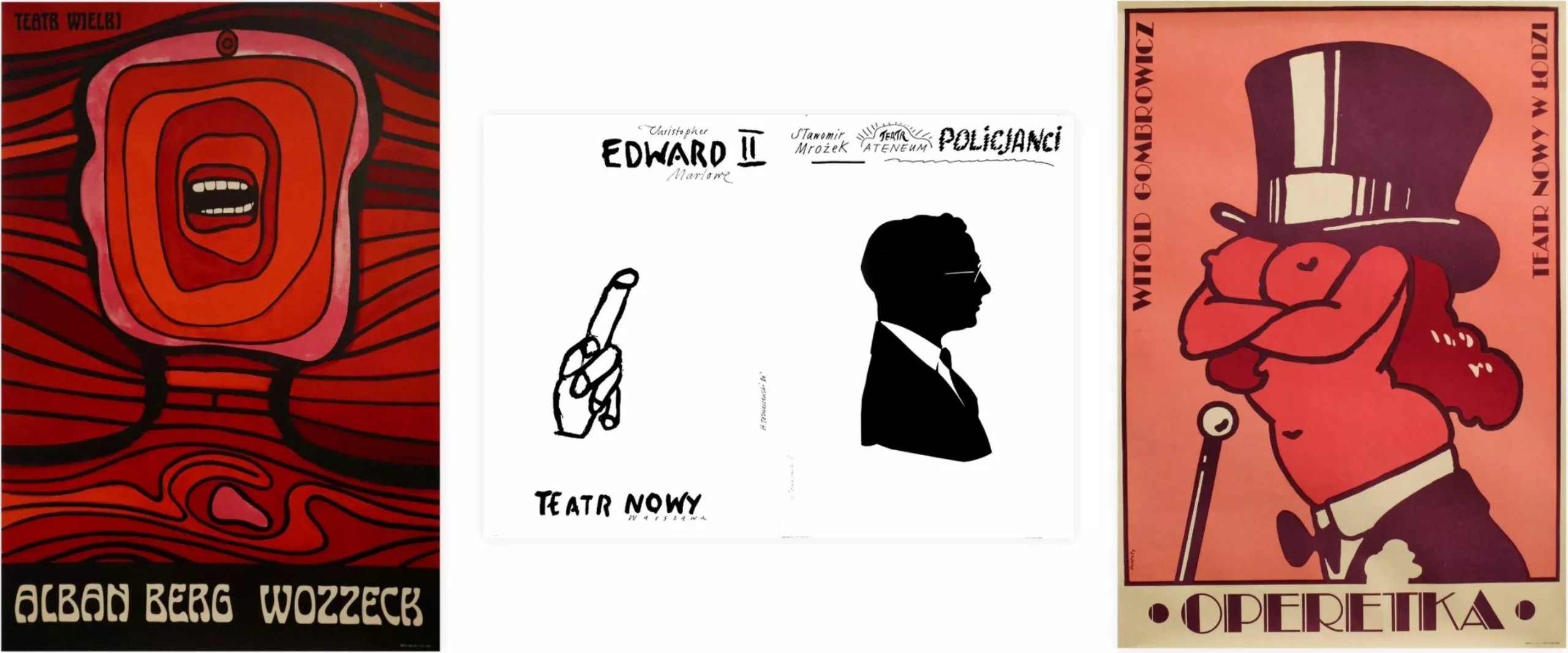

The decentralization of theater and the creation of National Dramatic Centers provided a favorable framework for the creation of bold posters. Cultural institutions quickly became privileged partners for graphic designers who wished to give their work a political dimension. It was at the turn of the 1980s that Grapus became involved with several theaters, including the Théâtre de la Salamandre in Tourcoing. The relationship that developed between the commissioner and the graphic designer went far beyond a simple response to a commission.

After ’68, after the utopias of a revolution to be built, graphic designers and theater people shared a close human and intellectual connection. They were part of the same movement, the same current of thought. The project of a new society was championed both by the director and by the graphic designer.

The image created had to convey this societal project. And the Théâtre de la Salamandre perfectly embodied this spirit. The theater aimed to be a “public thing.” The posters had to assert this claim. The collaboration between the Salamandre and Grapus continued from 1975 to 1982. “As for the way we worked and our goals, there was a certain similarity between the Salamandre and Grapus,” explained Pierre Bernard. “The collective working method, social and political awareness, reflection and questioning of our own work, play and analysis, entertaining and provoking thought. With the Salamandre, we were not working against the commissioner, but with them. At night, we would go out to paste up wild posters and do guerrilla posting—it was about taking concrete action to speak out in the city.”

In the wake of May ’68, the Grapus co-founders rediscovered the passion that drove them when they created posters in the Arts Décoratifs workshop.

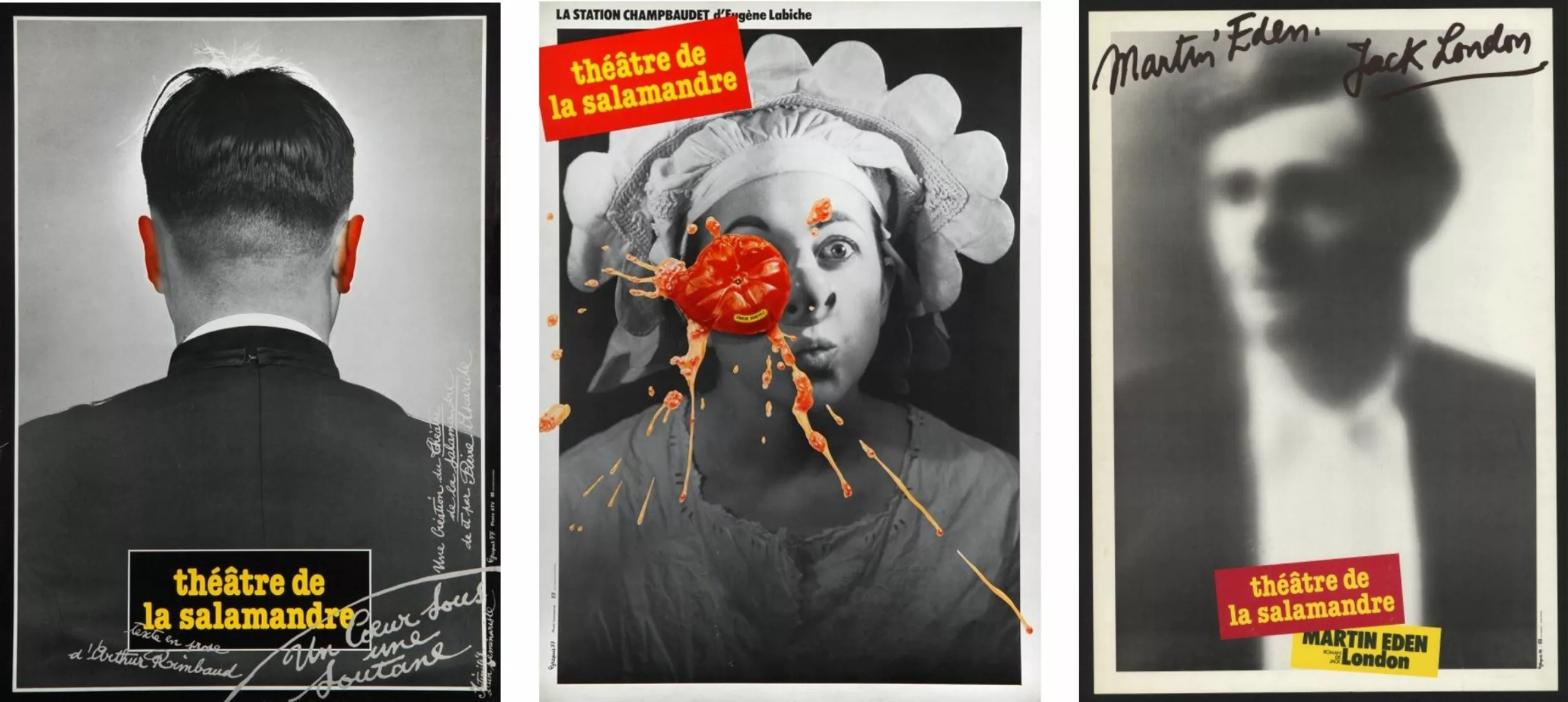

In a 2008 interview with the collective “Formes Vives,” Pierre Bernard spoke about the role of the poster. “With these posters for the Petit Odéon theater, we brought to life the theater’s issues within the city. They didn’t serve any informational purpose, but they were a form of civic presence. We showed that posters are there to signify that we are in a public space and that somewhere, something is happening that concerns us. You have to go there to become even more involved, but the poster is already the sign—and not just clean information.”

For the graphic designers of that time, the poster retained this role as an ideological breach in a society where consumption was becoming increasingly dominant.

Alain Le Quernec, the Passion for Posters

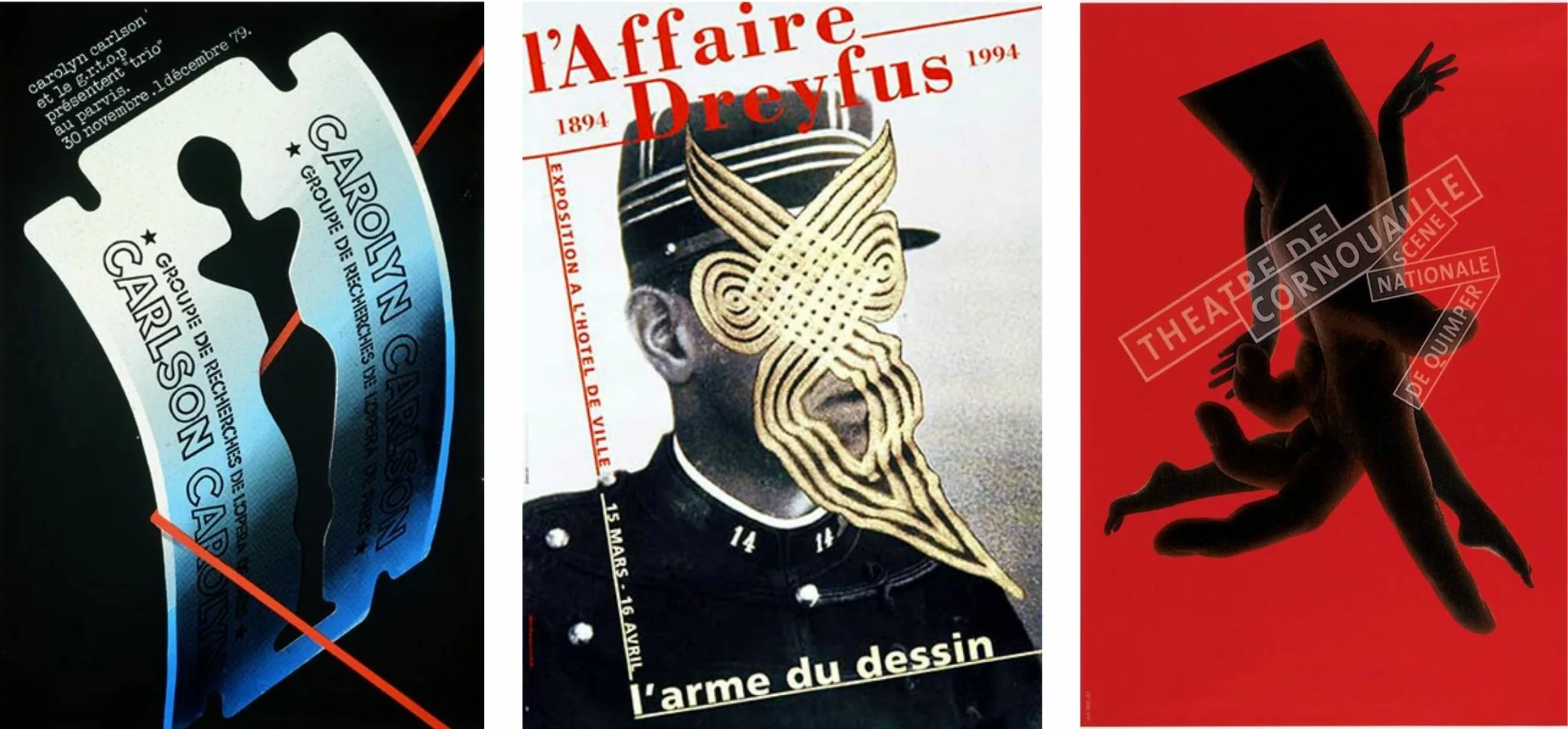

A few years apart, Alain Le Quernec was among those who went to Poland to join Henryk Tomaszewski’s workshop. He too drew from the tradition of Polish poster art and the idea of visual metaphor. From the very beginning, he dedicated a significant part of his work to culture. Many of his award-winning posters were—and still are—commissions for theaters, festivals, or concerts.

He appreciates the questioning of good taste and the popular. Far from wanting to create an elitist theater poster, it must be accessible and find the graphic style that best conveys the simple message he wishes to express. Le Quernec does not forbid himself wit or wordplay. Experimentation allows him to renew himself and avoid being locked into a particular style.

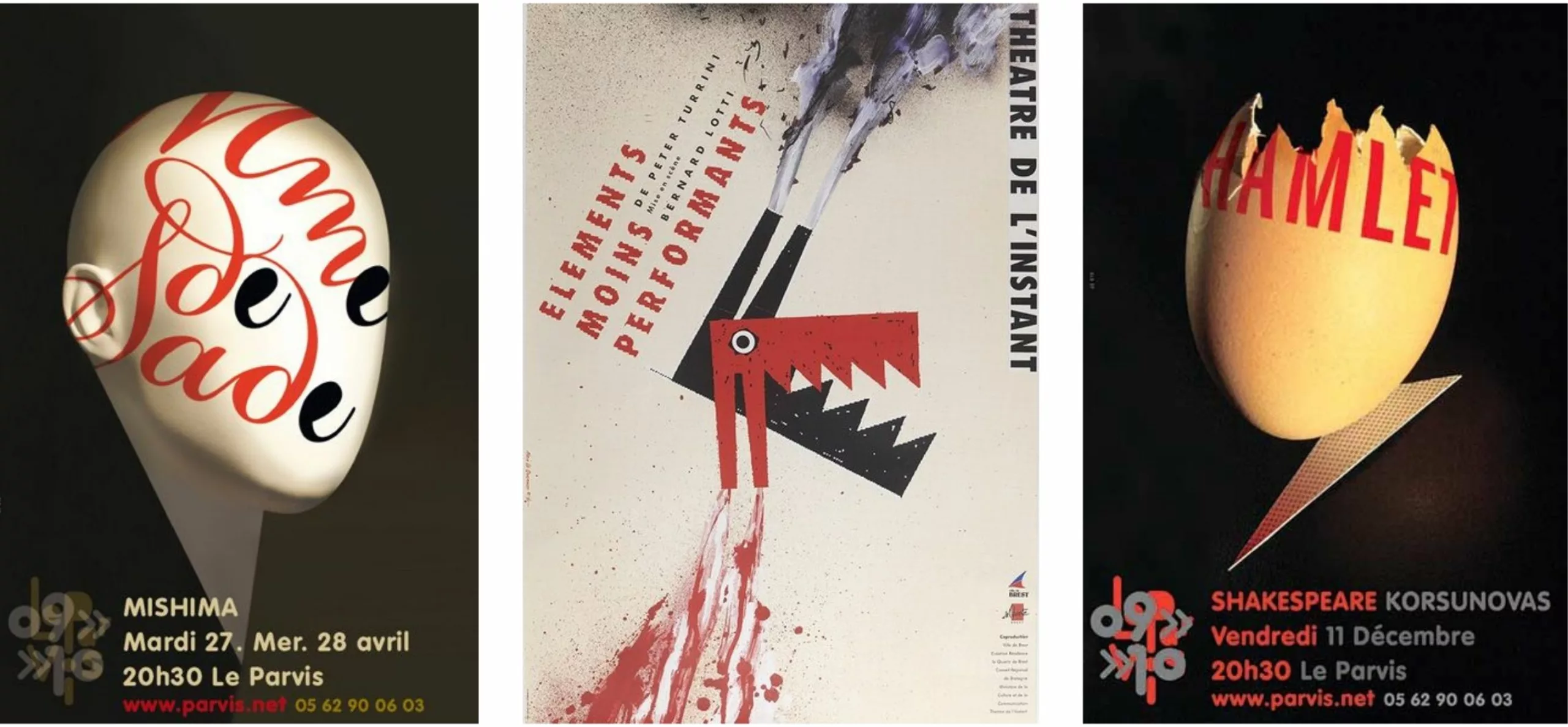

It was Bernard Lotti, director of the Théâtre de l’Instant in Brest, who gave him the opportunity to work on theater posters in 1981. This collaboration would last several years. Then came the Théâtre du Parvis, the national stage of Tarbes, the Rennes Opera, the Théâtre de Cornouaille in Quimper, and the more typographic Théâtre de Morlaix.

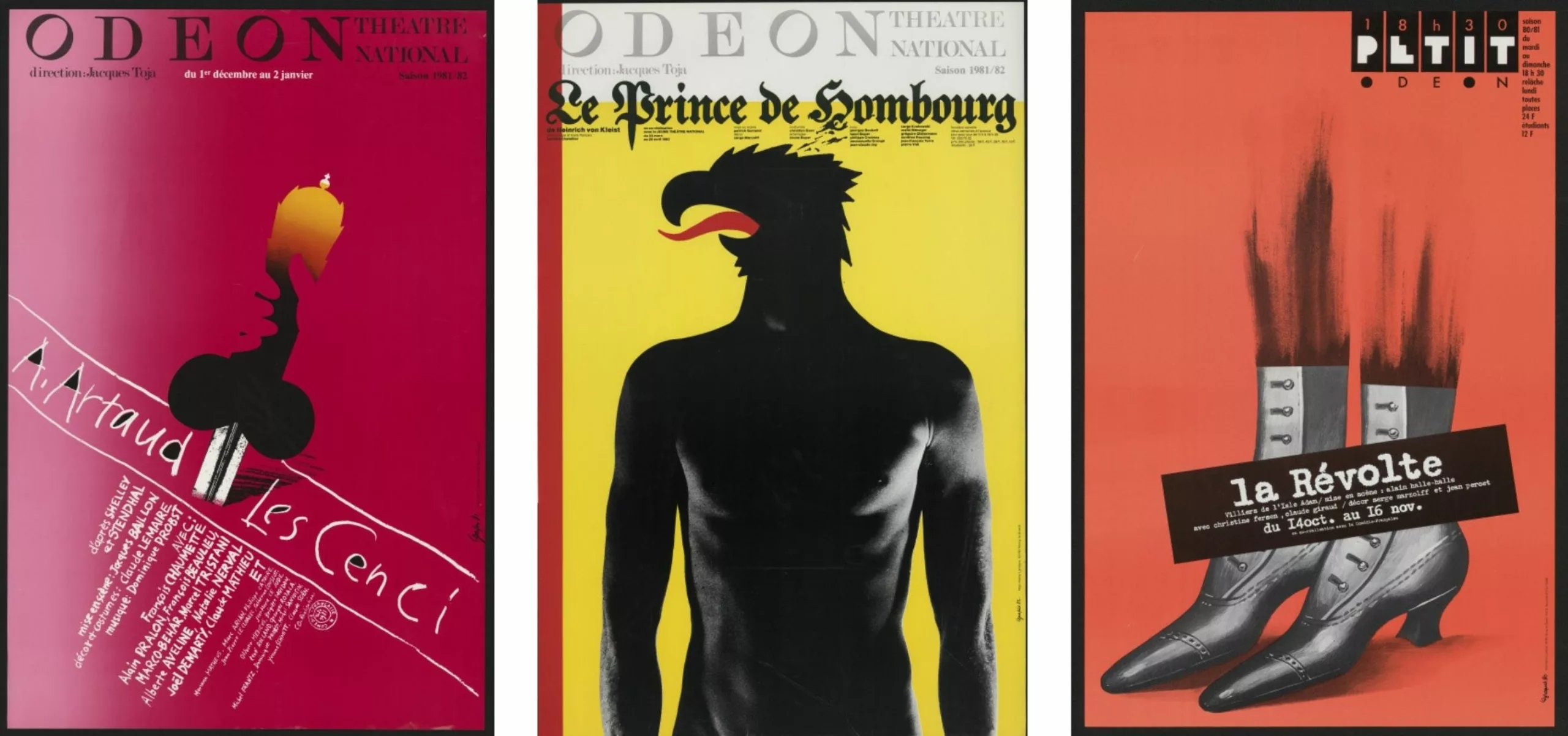

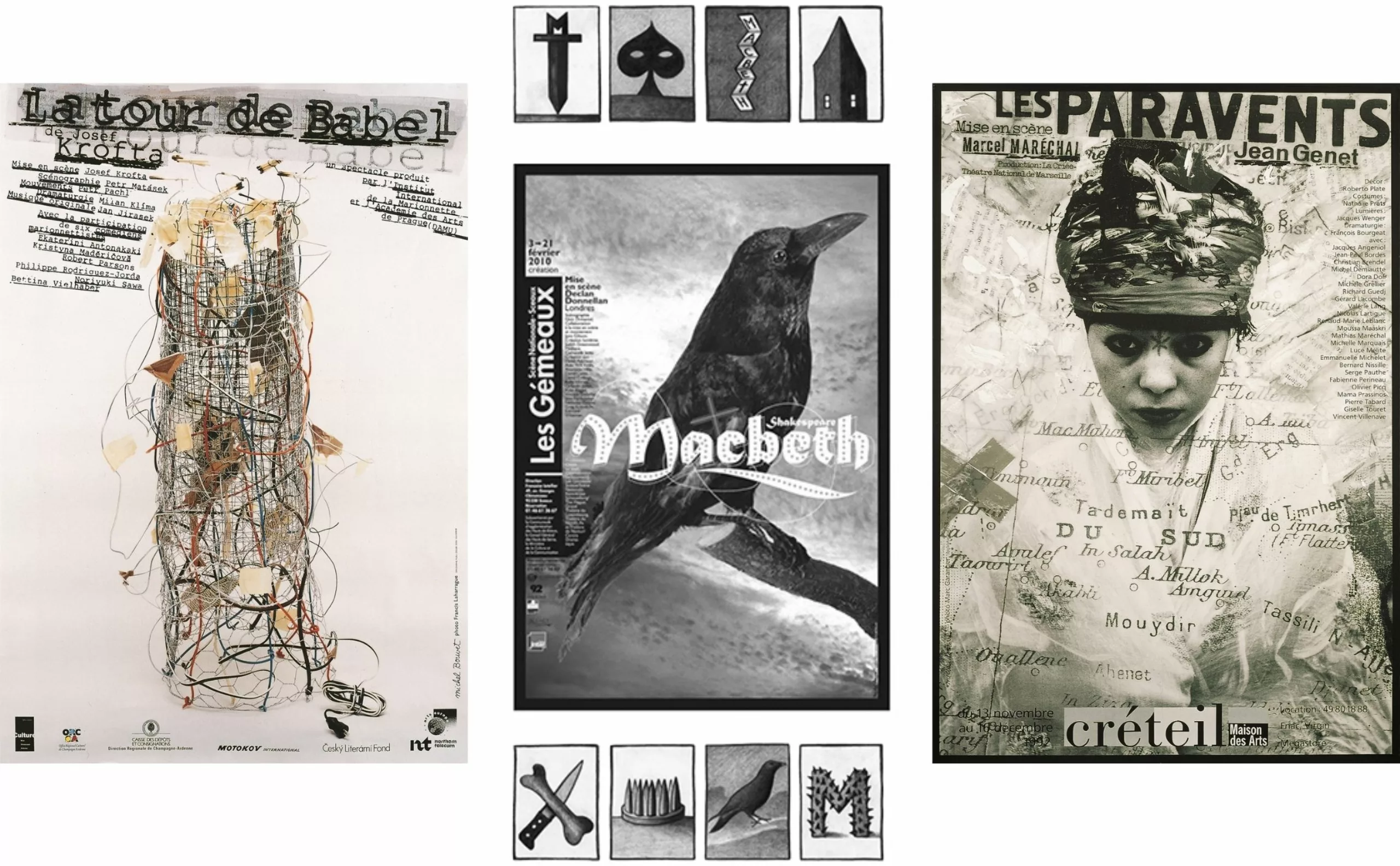

Michel Bouvet, the self-proclaimed poster artist

Michel Bouvet, for his part, belongs to a different generation than those who made the journey to Warsaw. Yet he too fits within this tradition of cultural posters based on visual metaphor. Even today, the image remains his primary concern. It was in Prague that he discovered the theater poster, and it was a revelation for him.

After studying painting at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, from which he graduated in 1978, he created his first posters in 1981 at the Maison de la Culture in Créteil. He was 25 years old.

Dans cette décennie 80 et au moment où Grapus fait autorité sur le graphisme en France, il va trouver une place toute personnelle. Les collaborations avec les théâtres vont s’enchainer. Sa reconnaissance franchira les frontières de l’hexagone avec de très belles expositions en Amérique du Sud, en Chine et au japon.

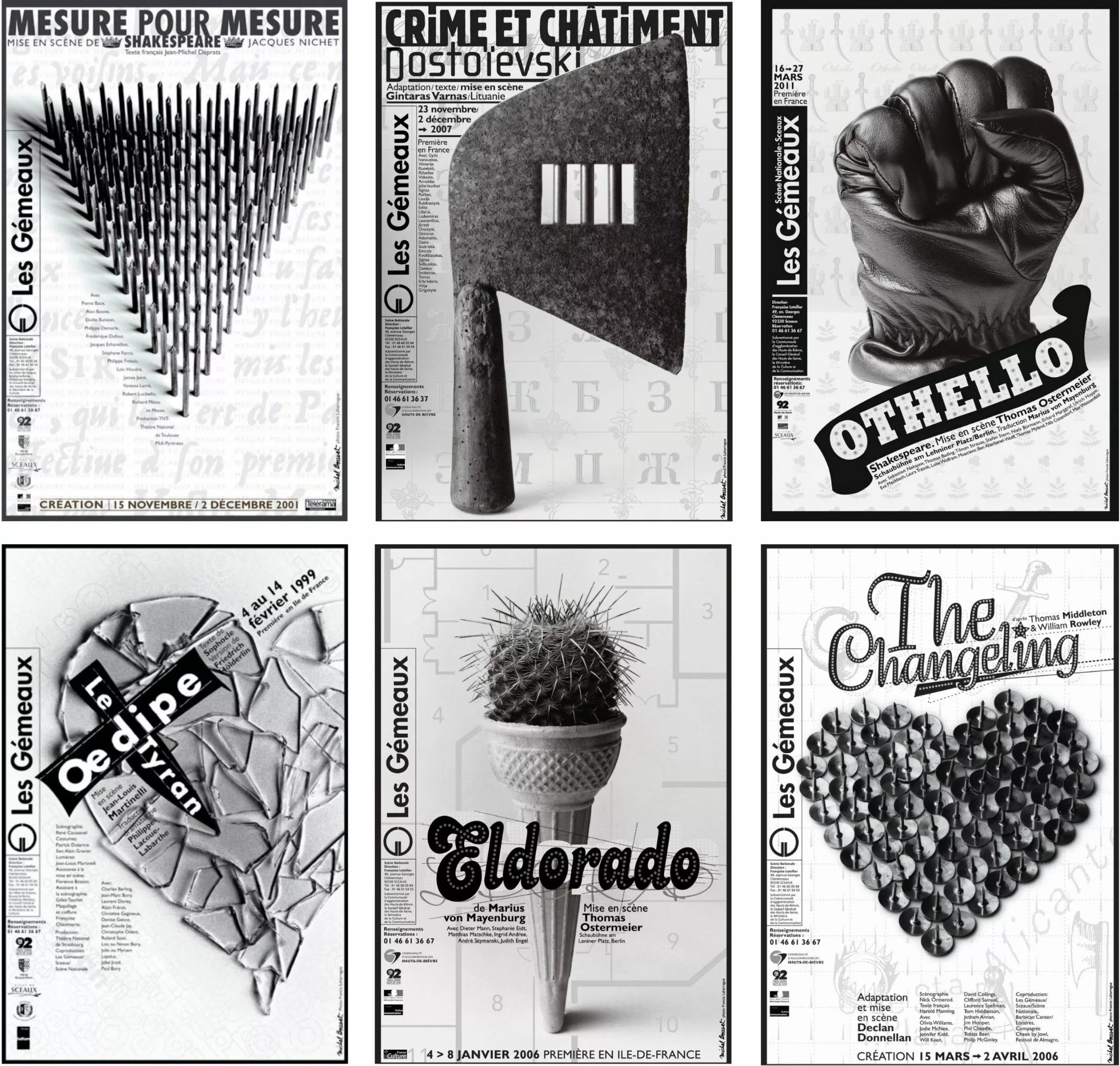

Michel Bouvet travaille avec le Théâtre des Gémeaux, scène nationale de Seaux, depuis 1992 (ce qui en fait sans doute une des plus longues collaborations d’un graphiste avec un théâtre). Cherchant à casser les codes, en 1998, il décide de créer des affiches en bichromie, noir + gris Pantone, ce qui va le distinguer immédiatement des autres affiches théâtrales, mais aussi des supports commerciaux. Depuis cette époque, il travaille les visuels avec le photographe Francis Laharrague.

In the 1980s, at a time when Grapus was the leading authority in French graphic design, Michel Bouvet carved out a very personal place for himself. Collaborations with theaters followed one after another. His recognition crossed the borders of France with impressive exhibitions in South America, China, and Japan.

Since 1992, Michel Bouvet has been working with the Théâtre des Gémeaux, the national stage of Seaux (which is likely one of the longest collaborations between a graphic designer and a theater). Seeking to break the codes, in 1998 he decided to create posters in two colors, black + Pantone gray, immediately distinguishing his work from other theater posters as well as commercial media. Since that time, he has worked on visuals alongside photographer Francis Laharrague.

For Michel Bouvet, it is not simply a question of illustrating a text. He seeks to take the viewer elsewhere. The visual metaphor enables this poetic and critical universe.

For example, in *Othello*, he highlights a fist wearing a Black Power glove—a reference to Tommie Smith’s gesture in Mexico in 1968—and thus questions the text by proposing a deeply personal updating.

For the Gémeaux theater, the image is generally accompanied by typographic work unique to each poster.

With the Opéra de Massy, a collaborator since 1993, he imagined in 2006 a new graphic language based on a more stylized and accessible visual metaphor, aimed at an audience that does not usually attend the theater.

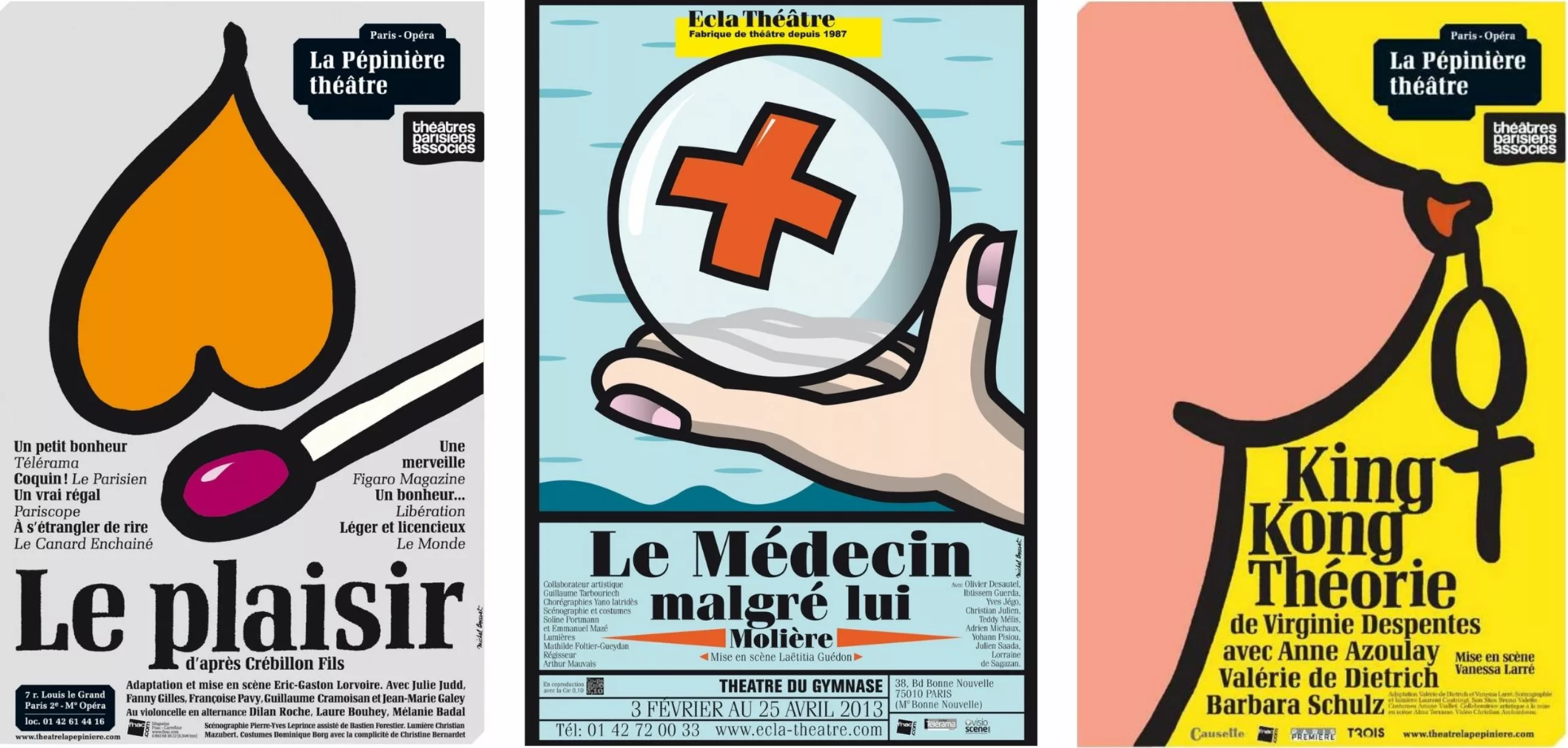

With the Pépinière Théâtre, he created his first posters in 2008.

In Act IV, we will explore the posters of the Théâtre de la Colline, from Batory to the ter Bekke & Behage studio.