Erecting the image of the penis: anatomy of an iconic symbol

Let’s cut to the chase. Behind toilet graffiti lies a visual, symbolic, political, and cultural totem that is much more complex than it appears. The penis, or rather its image, is everywhere, sometimes invasive, often trivialized: in art, on the streets, in advertising campaigns, in fashion, in toilets, in coded messages, in emojis… It spans the ages, distorting, hiding, exposing itself, erecting itself, according to civilizations, artistic styles, taboos, liberations, or censorship.

The penis is invisible and yet omnipresent, a great silent phallocrat of our visual culture. While breasts, vulvas, and other symbols of the female body have undergone a feminist and artistic reinterpretation in recent years, the male sex remains a prisoner of its symbolic charge, oscillating between obscenity and omnipotence.

What if we decided, once and for all, to analyze this graphic organ despite contemporary taboos? To decipher the intentions, the misappropriations, the unspoken? In 2018, Graphéine broke taboos by dedicating a visual history to the female sex. This time, let us immerse you in the representation of the penis through art, design, street culture, and symbols.

The aim of this article is not to list penises in art (Wikipedia already does that very well), but to understand what we project onto this visual symbol. What our era says about it. What its representation provokes or allows today. Between ancient graffiti and suggestive emoticons, we offer here a graphic, semiological, and social exploration of an organ that has become an icon.

The penis throughout history, from caves to talismans

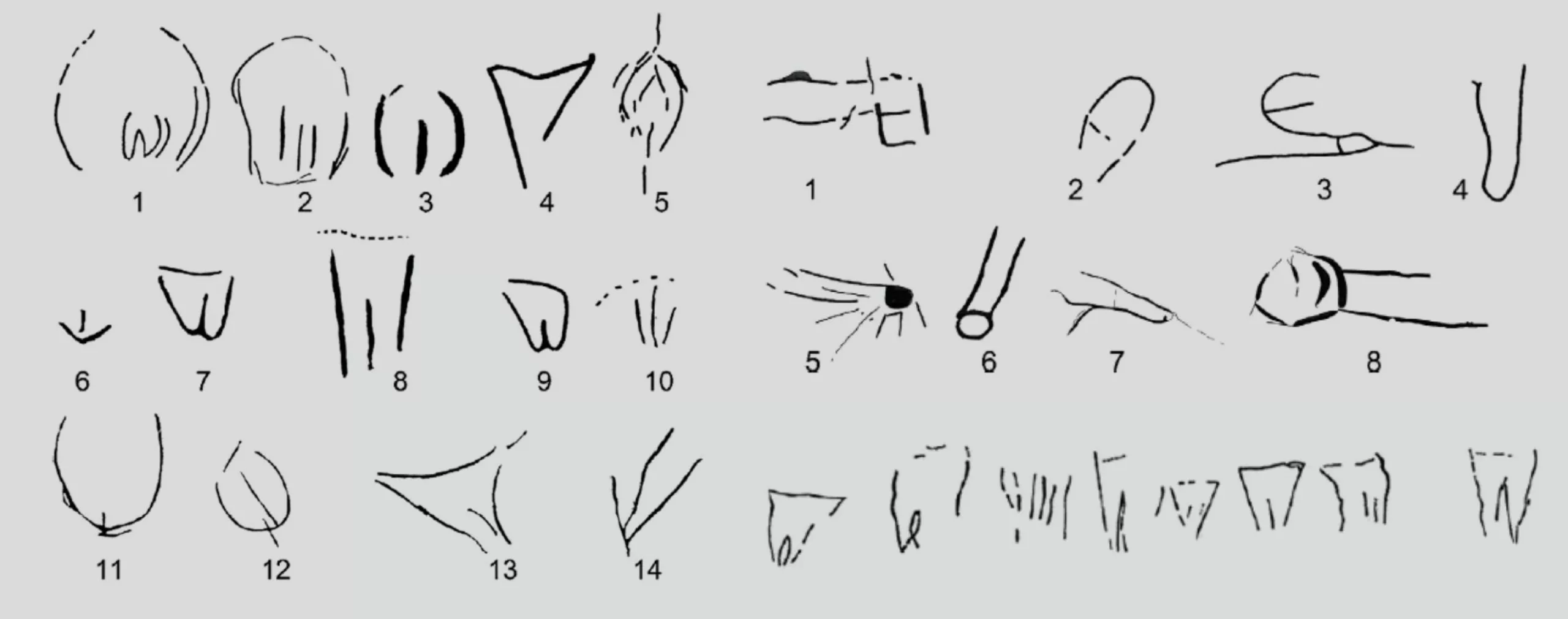

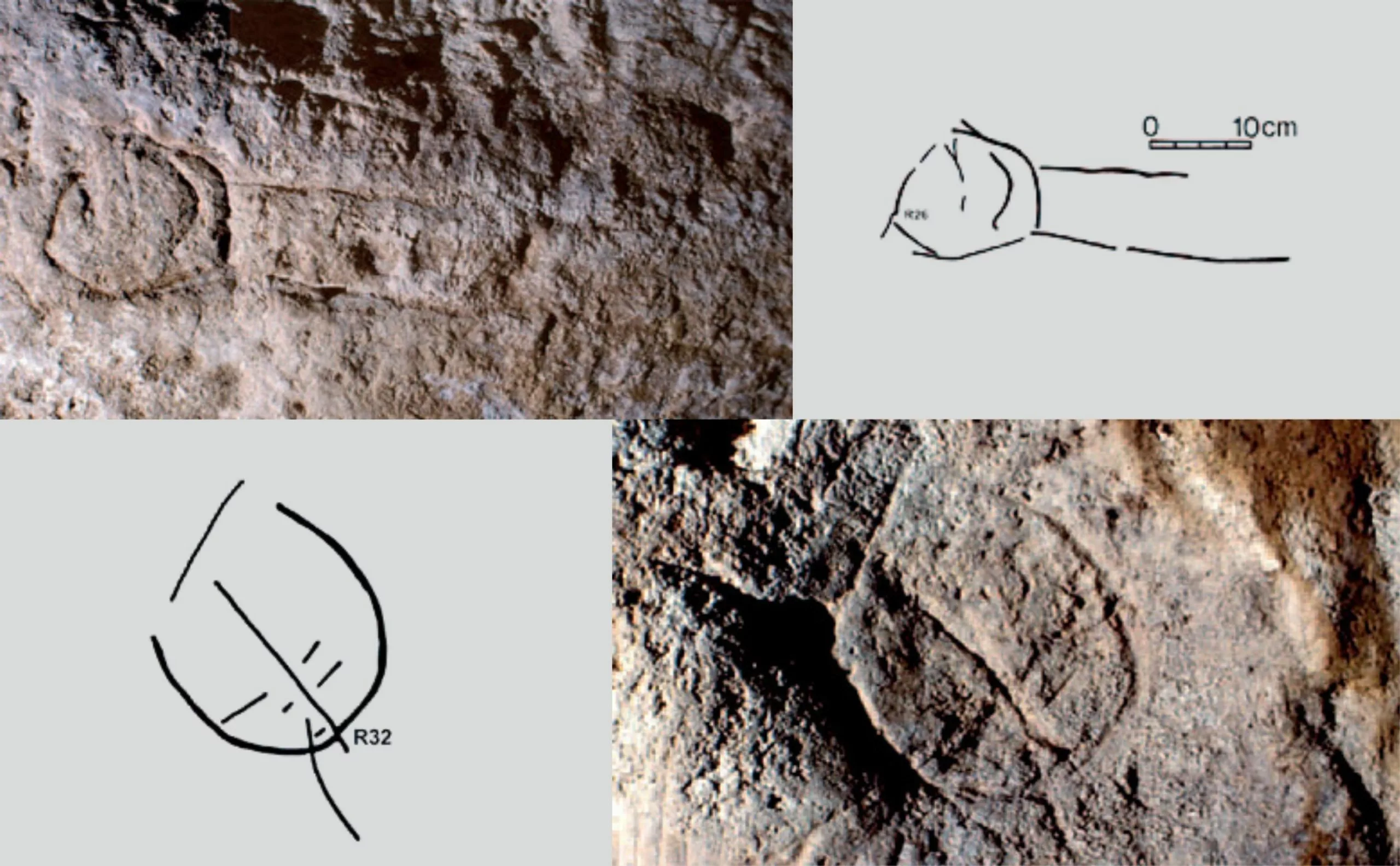

Before becoming graffiti on high school walls or mocking drawings on urinals, the phallus had long been a fascinating and probably protective or sacred symbol, much like the female sex. Found engraved on the walls of the La Marche and Chauvet caves during the Paleolithic era in all sorts of different forms, it was nevertheless less popular than vulvas, which were represented much more often (according to the inventory of Brigitte and Gilles Delluc). Today, however, the opposite is true, with penises appearing 10 times more often in public spaces.

The vulva and penis are thus probably humanity’s first pictograms: we talked about this on Arte in this episode of Le dessous des images on Olympic pictograms at minute 8.

From the Hermetic pillar to Priapus, well-endowed deities

Later, in Greco-Roman civilization, representations of the penis were far from hidden: they were displayed and even exalted. The Greeks in Athens had hermaic pillars, stone markers bearing the image of Hermes that stood in the urban landscape. They were decorated with the bust of the god up to his shoulders and an erect phallus halfway up. These pillars marked roads and crossroads and protected public spaces, Hermes being the god of travelers and fertility.

The penis is frontal, unapologetic, never vulgar. It is a sign of power, divine virility, fertility. At the time, sex was not displayed for sex’s sake: it was signaled, commanded, sanctified.

The penis even had its own god: Priapus, the deformed son of Aphrodite and Dionysus. His oversized penis served three purposes: protection, fertility, and comedy, as gods and passersby mocked his disability. As the god of gardens, statues bearing his likeness scared birds away with their protuberance. Dionysus himself was “born from the thigh of Zeus,” an ancient euphemism for the latter’s phallus…

Phallophories were also organized for the god of wine and vine fertility: processions in which a huge wooden phallus was carried. An original and somewhat cumbersome way to commemorate his dismemberment by the Titans, after which only his “heart” (meaning his penis) was found and eaten, before he was reborn (Dionysus means “twice born”). This story is inherited from that of Osiris.

Today, you can find pins featuring this motif on Etsy…

A little fascinating etymology with phallic branding

A symbol of fertility, power, and protection against the evil eye, the phallus was omnipresent in ancient Greece and hammered home like a logo, a truly sacred and fascinating brand stretching from votive architecture to jewelry, fountains, and frescoes in merchants’ villas.

Children were not spared either, as they were given amulets decorated with winged penises, called fascinums, to wear around their necks to protect them from the evil eye. These lucky charms warded off evil spells by embodying this protective member, which was also hung on the front of victorious chariots… the ancestor of car mascots, in short!

Fascinating, you might say? And you would be right, since the term “fascinating” comes from these phallic charms and means “to use the power of the fascinus (which refers to the phallus), to practice magic, to enchant.” It has the same ancient meaning as mascots, mascoto meaning “bewitchment.” Coincidence? Were car mascots also used to protect against the evil eye?

Bird names in all languages

But why winged penises? The penis and wings are the attributes of Hermes, messenger of the gods. He travels freely between the heavens, home of the gods, and the earth, home of humans, linking the two worlds. It is perhaps not so surprising then to note that the penis is often referred to by bird names in several languages. It is called cock in American English, polla (hen) in Spanish, pinto (chick) or roula (dove) in Portuguese, poulakis (little bird) in Greek, 屌 diao (bird) or 雞 ji (chicken) in Chinese…! Is this a Greco-Roman legacy? Taking this even further, since nothing is stopping us, could we say that airplanes, which also often bear bird names such as falcon, hawk, eagle, etc., are our contemporary fascinums, winged penises that fly through the skies like messengers of modern gods?

To continue with this somewhat far-fetched etymological line of reasoning that brings everything back to the phallus, the term “branding” would have the same root as ‘brandir’ (to brandish a weapon) or “branler” (to jerk off) (to move, shake… originally, a weapon), we talked about it in this article.

From the Middle Ages to today, from trivial sex to hidden sex

In medieval Europe, nudity was not erotic, it was trivial and was used to make people laugh, to punish, or to protect. It is difficult to understand the descriptive, ironic, or banal role of these images in our current civilization, which is both prudish and sexualized.

The protective talisman of medieval pilgrims

Twelfth-century pilgrims wore insignia, metal figures that they attached to their clothing without any shame. Crowned vulvas, phalluses in profile, rural coitus, winged rods, pilgrim vulvas with hats and staff rods, and flower vulvas are just some of the possible variations. “The desire to protect oneself from evil or ward off the evil eye was expressed through various means, such as insults, amulets, incantations, or collective rituals. Among these means of protection, images have played an important role in the West, and among these images, those of sexual organs or the sexual act are at the forefront of protective motifs,” according to the book Image et transgression au Moyen Âge (Image and Transgression in the Middle Ages).

As with the Romans, “sex is just one motif among others for dispelling bad luck or protecting an area. It shares this function with saints, the Virgin Mary, the crucifix and more ambiguous figures found on certain gargoyles. Such images can be found on the entrance pillars of buildings, on doors, in manuscripts, as the guardian figures of the evangelists and perhaps even certain monsters in the margins.” (Excerpt from Image and Transgression in the Middle Ages.)

It was said that female genitalia “chased away demons, stopped storms or, more prosaically, destroyed harmful insects, according to Pliny,” explains Claude Gaignebet. Don’t move, we’ll bring the mosquito repellent.

Sex in the margins

Scribes did not hesitate to mock the penis. In the margins of medieval manuscripts, known as marginalia, we find deformed, comical, and sometimes literally armed penises. There is a whole semantic bestiary in which the male sex becomes the object of absurdity, satire, and reversal, with drawings of women riding giant phalluses like dragons, nuns picking testicles like apples, or mysterious animals wearing phallic-shaped headgear. See for yourself:

In these manuscripts, vellum (calfskin parchment) or sheepskin pages were worth a bollock (pardon our French), and writing in Gothic script saved considerable space, allowing the text to be condensed onto the pages. Copying sacred texts was a long and tedious task, and the margins provided a convenient outlet for creativity. The penis, therefore, was exiled from the text, where scribes could let off steam after several hours of calligraphy. Was it for laughs? For protection? To let loose in this chaste universe?

Researcher Michael Camille refers to this marginal religious pornography as an alternative form of expression, outside of dogma. In the margins, therefore in the interstices of power. A kind of sacred counter-design.

The birth of pornography, thanks (?) to the Church: prohibiting in order to better show

But medieval Christian Europe gradually made representations of sex invisible around the 15th century. The penis became taboo, a guilty impulse, an object of shame as the Catholic Church became increasingly uptight about the subject. Sex was a sin; the phallus was a weapon of the devil, as was the vulva, an organ of witchcraft. This smacks of trouble. “Their connection to the earth and the cosmos is severed and they are reduced to naturalistic images of banal eroticism, (…) where the lower body is amputated from its vitalistic dimension,” writes M. Bakhtine.

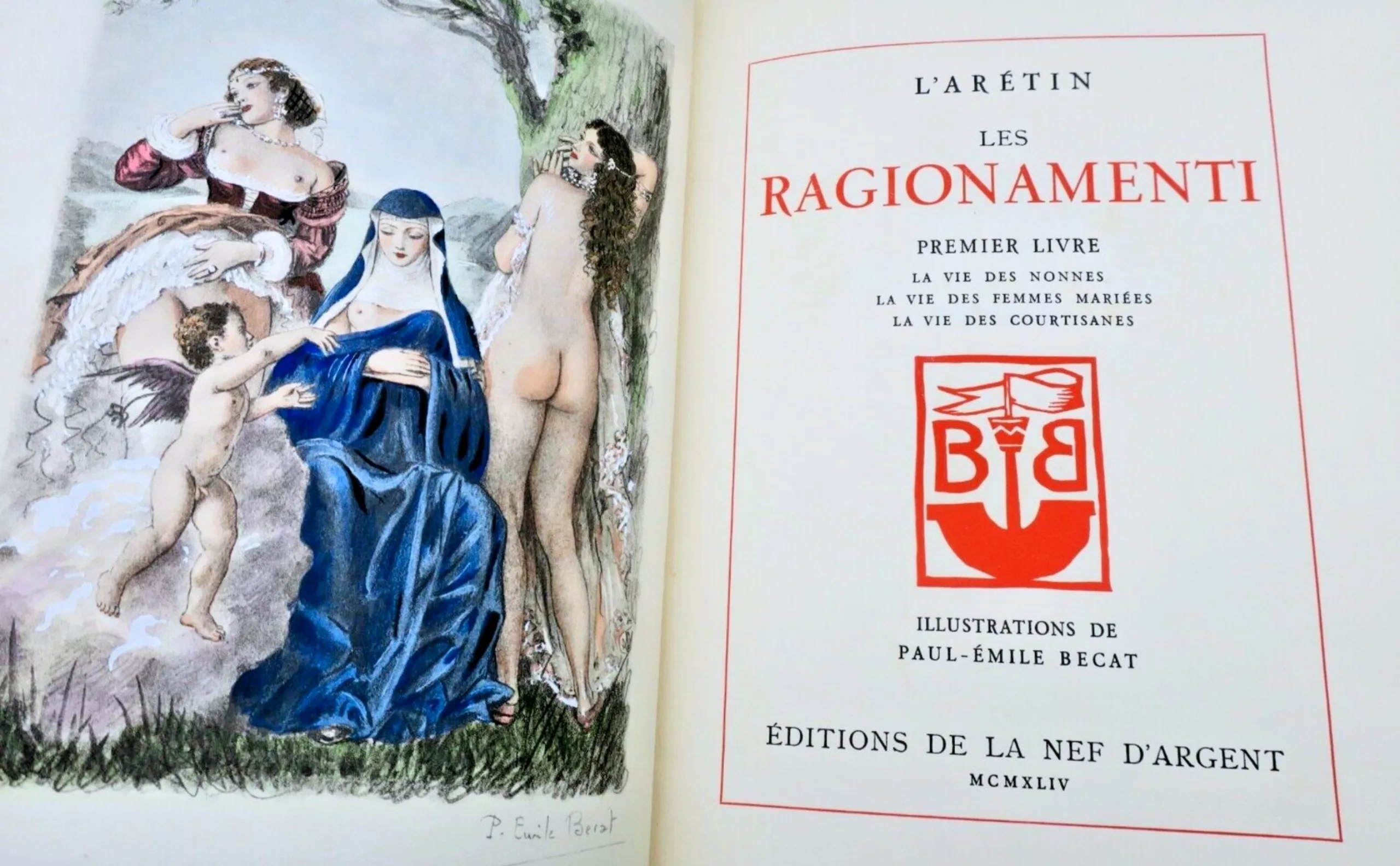

Church officials considered these representations indecent and “inciting debauchery,” as Antonin, Archbishop of Florence, criticized around 1450. “Everything related to sex and excrement, the ‘joyful matter,’ is reduced to its negative pole by morality.” By shifting from the sacred to the erotic, these images opened up a whole new visual field: pornography, with Aretino’s Ragionamenti, around 1534-1536, considered to be the first work written in this field.

“By reducing sex to its sensual and erotic aspects, the Church paved the way for the emergence of pornography” (Image and Transgression in the Middle Ages): who would have thought? Without prohibition, there can be no transgression; without transgression, there can be no eroticism!

All attempts to conceal, censor, or suppress information often achieve the opposite result: the hidden object becomes much more visible and attractive, precisely because of the attempt to conceal it. This is known as the Streisand effect.

Nevertheless, the penis gradually disappeared from public places and paintings, or was castrated, concealed by a drape, a fig leaf, or a modest hand. This physical disappearance gave rise to a symbolic presence: it was implied, guessed at, or forbidden. It was the golden age of graphic allusion. Gothic architecture, with its penetrating spires and lewd gargoyles, often says more than it shows.

Camouflaging penises with eggplants in the 21st century

In the 21st century, the phallus continues to hide and suggest itself through a digital double: the eggplant emoji. Having become a coded language for the phallus, the eggplant, banana, or carrot say a lot about our discomfort in naming or accepting it. Omnipresent since time immemorial, the penis is invisible (except in dick pics) amid widespread hypocrisy. This social taboo reached its peak when Google invented the “Quickdraw” project, a database of 50 million user-generated digital drawings, in which the world’s oldest iconic shape is simply never mentioned! “What about me, what about me, what about me?” it seems to sing.

In response, the Moniker studio created the website www.donotdrawapenis.com, which serves as an appendix to complete the collection by asking people not to draw… dicks (to highlight the absurdity of the situation).

Whereas the eroticized breast is fighting to be seen as nothing more than that (see the #FreeTheNipple movement), the penis remains pixelated, blurred, avoided, or replaced in images. The proliferation of phallic emojis shows, however, that while the need for representation persists, it is changing. The emoticon is no longer an object of power: it is a wink, an irony, a code that is no secret to anyone.

If talking about sex is disturbing and makes people uncomfortable, it is hard to imagine that there was a time not so long ago when it was talked about openly, or that there are countries where it is discussed freely. Besides, what a strange idea to write such a long article on the subject. But as they say, it’s not quantity that counts, it’s quality. (Will this avoid Google’s censorship?)

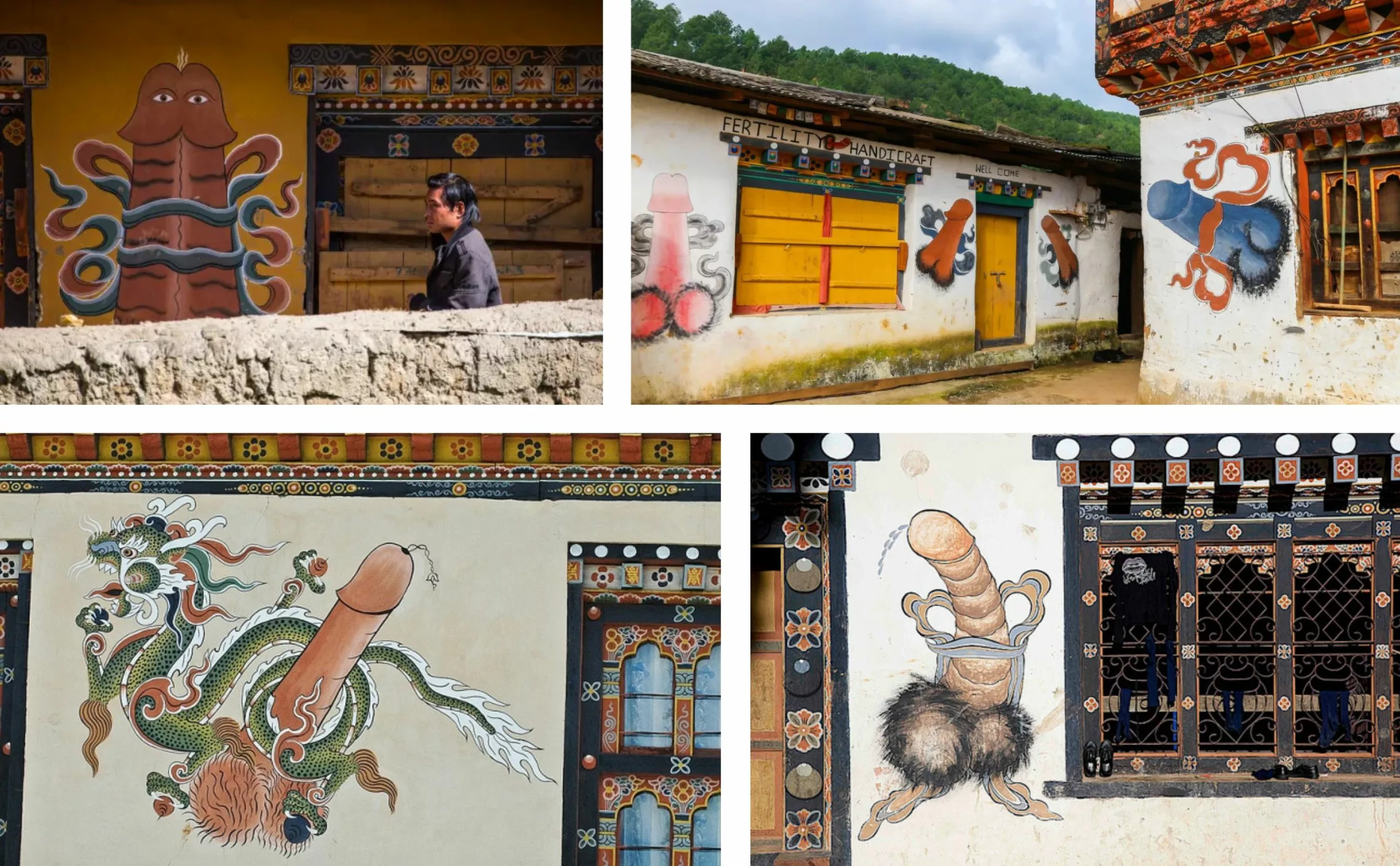

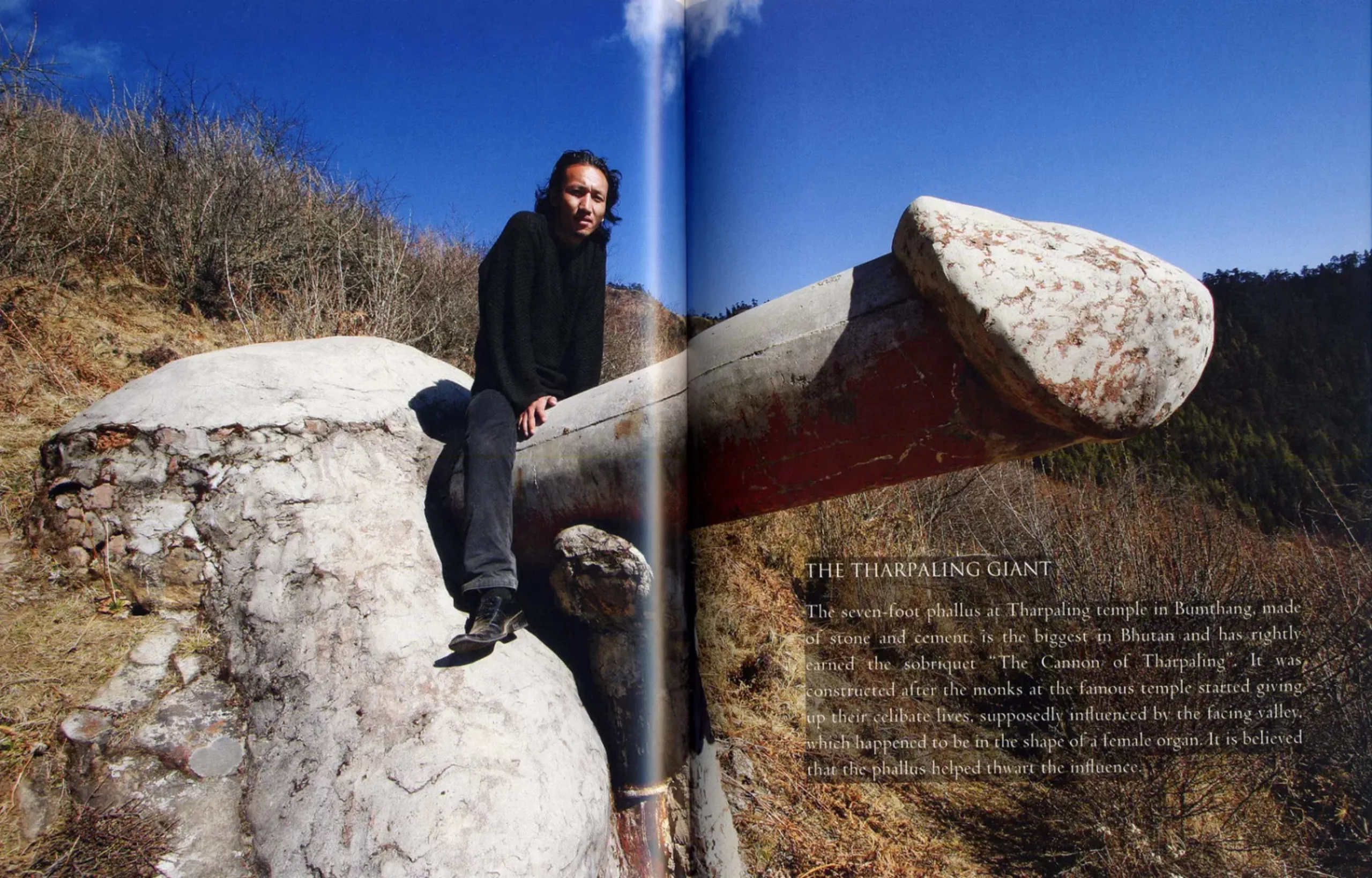

In Bhutan: phalluses that protect

Not all cultures share the Western modesty towards the phallus. Nordic countries call a penis a penis and have no qualms about talking about or showing phalluses. In Bhutan, a landlocked kingdom in the Himalayas, penises are literally painted on walls. Large, pink, flamboyant, often winged, sometimes spitting fire or semen. Far from being obscene, these colorful representations are symbols of protection, inherited from the monk Drukpa Kunley, nicknamed “the divine madman,” who advocated a joyful, irreverent, and highly sexualized form of Buddhism. He is said to have brought Buddhism back from Tibet and defeated a demoness with his member, which was given the sweet name of “magic lightning of the wise woman.” He is said to have brought Buddhism back from Tibet and defeated a demoness with his member, which was given the sweet name of “magical lightning bolt of wisdom.”

Today, women seeking fertility come to bang their heads against a wooden phallus while circling the monk’s temple. In rural areas, tradition dictates that five phalluses be hung at the four corners and ceiling of new houses as a form of protection. The phallus is a graphic talisman, a visual mantra against evil spirits.

These Bhutanese phalluses are standardized but unique, hand-painted, halfway between religious icons and punk stickers. They can also be found in Thailand and Bali.

They pose a fundamental question for visual cultures: where does the obscene end and the sacred begin? In our sanitized cultures, could we still imagine such uninhibited, powerfully local graphic communication?

Urban bitology: graffiti, tags, and sexpression from the street to the moon

While the penis is rarely displayed elsewhere as a sacred organ, it is universally embodied in a wild and furtive symbol: penis graffiti, which has become an icon over time. This primitive graffiti crosses cultures in its perpetual erection, as representations “at rest” are rare.

The penis heads of Pompeii

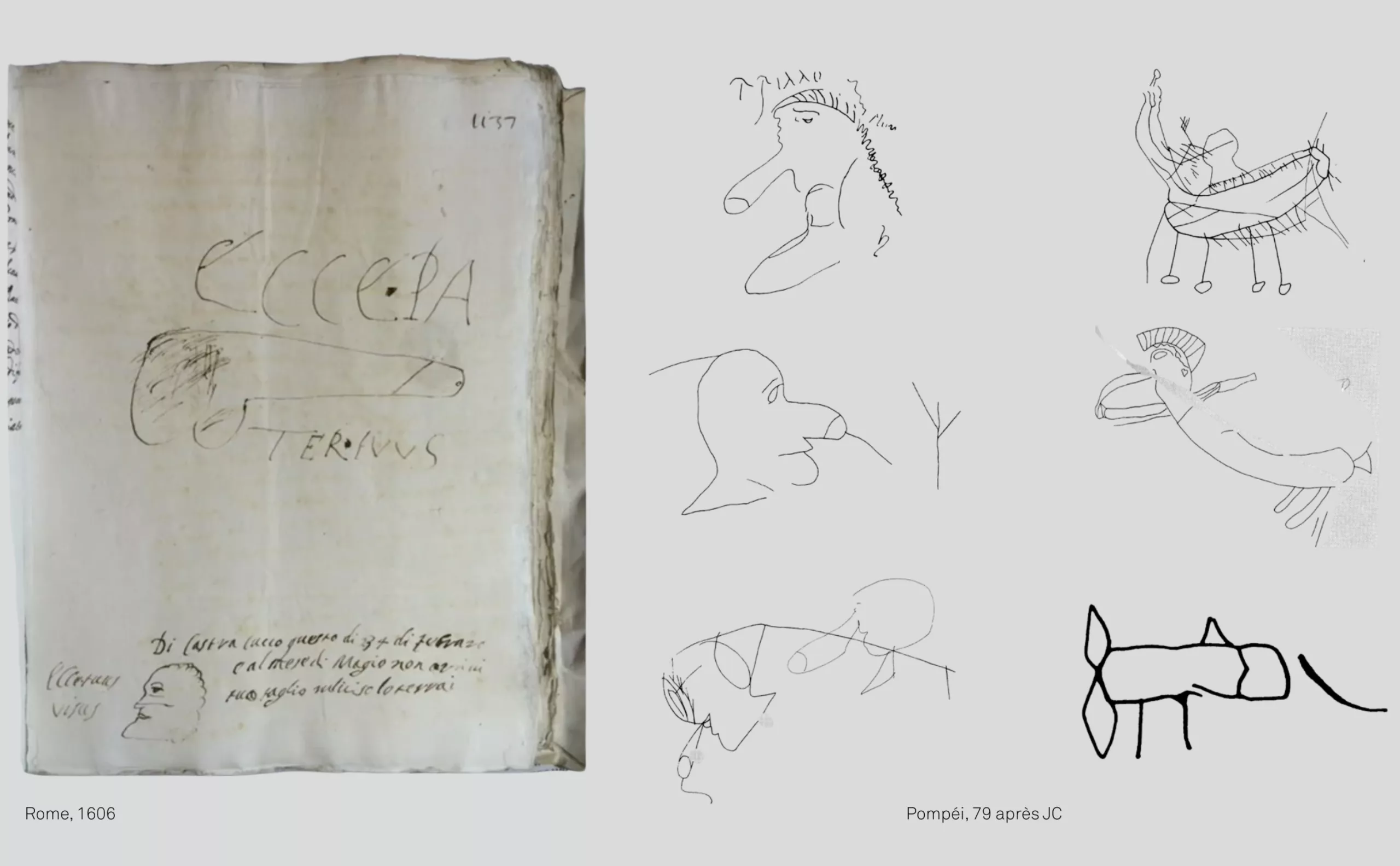

In 16th-century Rome, as Coline Sunier and Charles Mazé explain in their excellent lecture Sex Symbols, drawings of penises were displayed in cartelli infamanti, defamatory posters used to insult one’s enemies (see image below left). Anonymous, they were plastered in the street for the attention of a particular person, or used as a protest. As defamation was considered a crime, the police kept these strange pieces of evidence in their records…

But there were also numerous drawings of “dick heads,” men with phallic-shaped noses, found on the walls of Pompeii as early as 79 AD and still drawn on walls today with probably just as much passion.

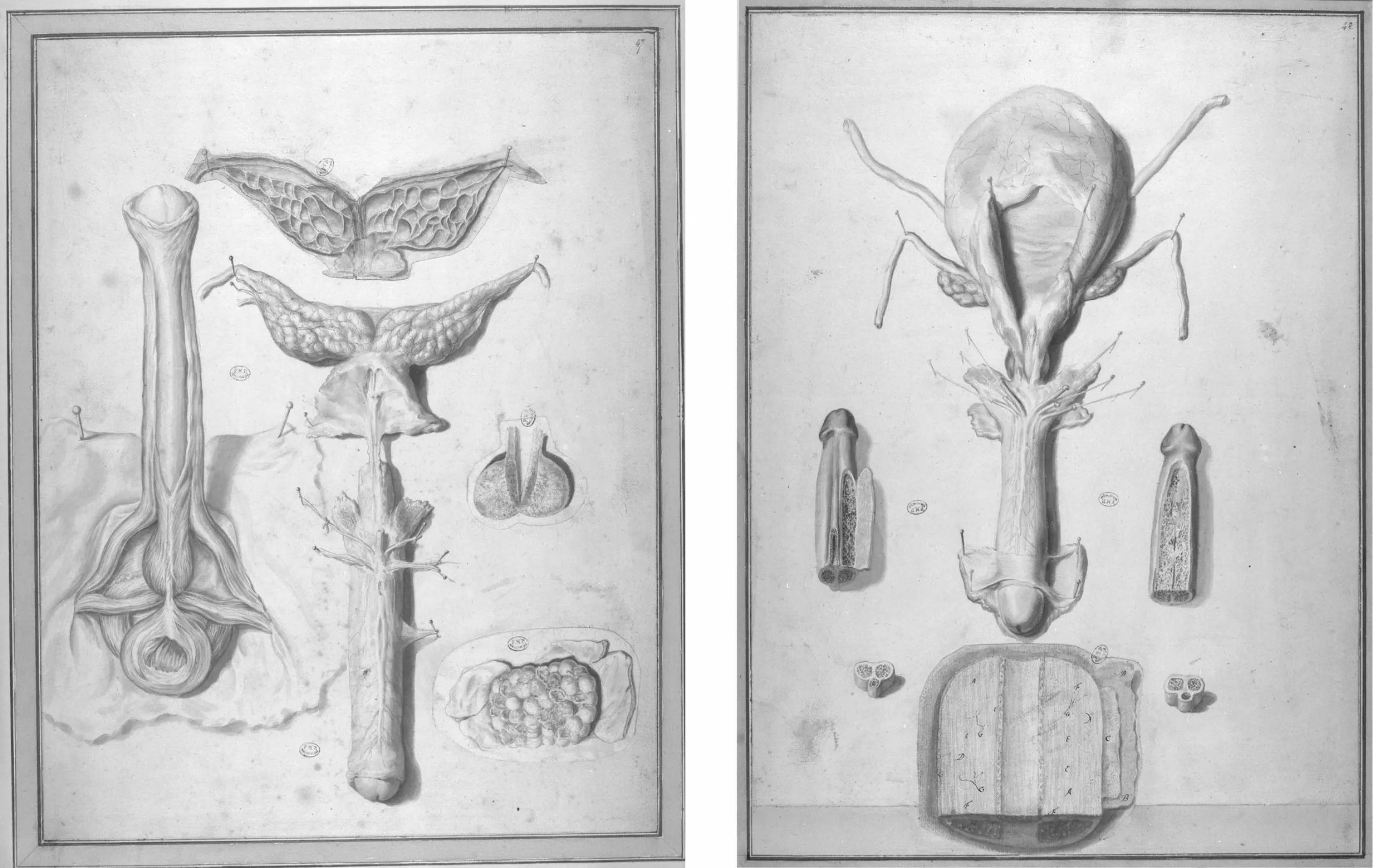

Incidentally, have you noticed that Roman penises were almost exclusively drawn in profile? The drawing of the penis “seen from above” as practiced today is said to have been inherited from medical illustrations that, starting in the 16th century, divided the penis into anatomical sections (as shown below, taken from the Paris Cité University library). Who still draws penises in profile? We leave it to the most avant-garde among you to take up the torch.

Living and reigning in public spaces today

By drawing penises, we express ourselves foolishly/bestially and challenge graphic and social order. But why this obsession? Is the tagged penis a graphic and assertive impulse or a marker of territory? In urban spaces, penis graffiti is like a cry of presence. A primitive mark to say “I am here.” Penis tags are provocative, posturing, a sign of belonging or exclusion. And sometimes even a protest.

Where political graffiti seeks to denounce, dick drawings seek to disturb, embarrass, pass the time, mock, or remind us of the presence of this virile attribute by violating public space, inserting something private and intimate into it. In response to this graphic provocation, many feminists tag vulvas on walls to reclaim this essentially masculine space.

This urban symbol embodies the very idea of branding: the act of affixing a mark, a brand, and thus communicating through a visual sign that is recognizable to all. You place your coat of arms on conquered territory. You place your logo to identify your brand. You draw a dick on a bench, a wall, a door, to inhabit the space.

And from Rome to Paris, the street penis is almost always identical: two testicles, a shaft, sometimes a few hairs, rarely any talent.

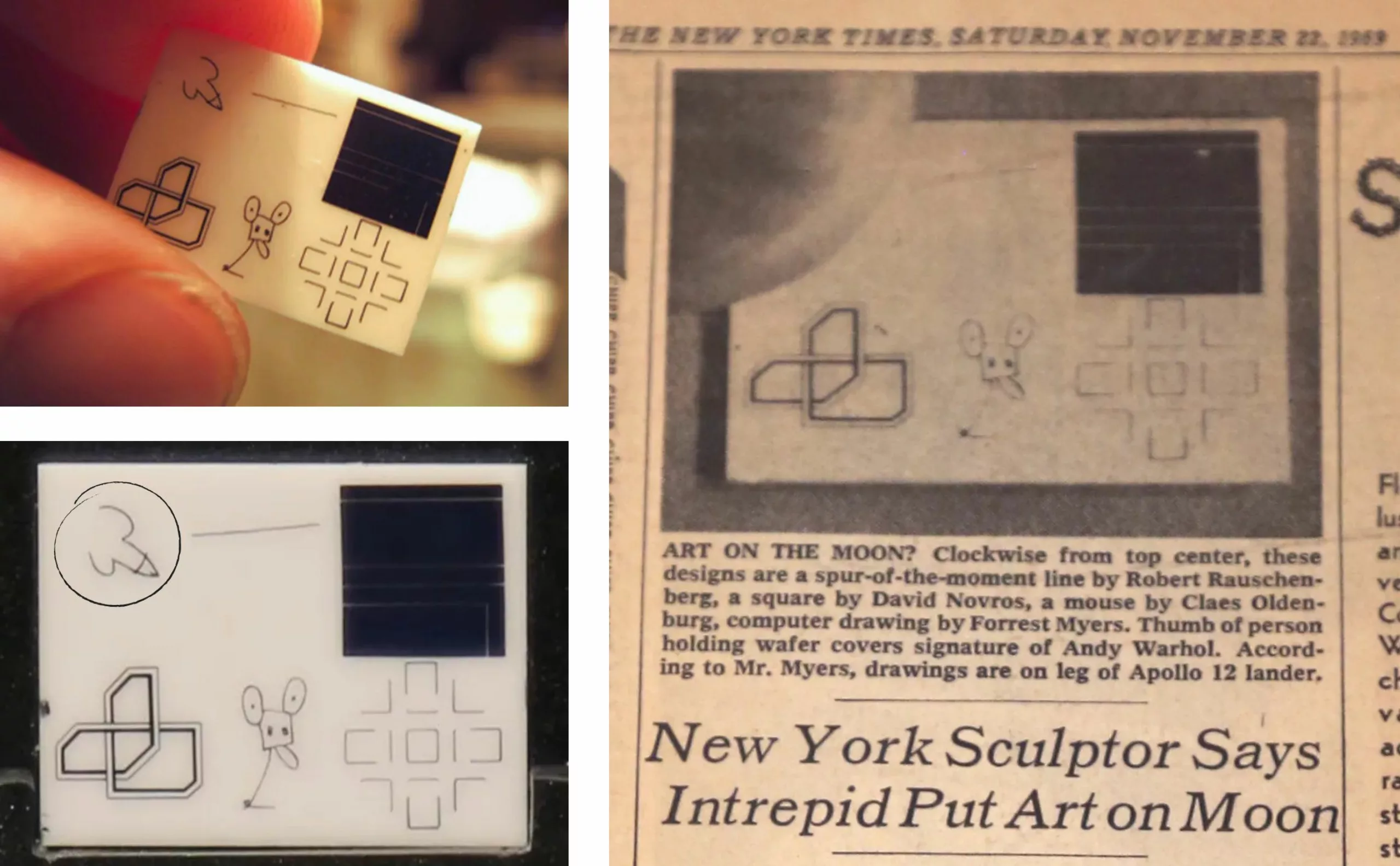

A small dick for man, a big dick for humanity

But did you know that we also sent a graffiti dick to the moon? In 1969, sculptor Frosty Myers insisted that NASA send a “tiny museum” to the moon, featuring the works of six artists: John Chamberlain, Forrest “Frosty” Myers, David Novros, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol. With no response from NASA, the chip was smuggled aboard an Apollo 12 lunar module. NASA responded by saying, “If it is true that they succeeded clandestinely, I hope the works are the best of contemporary American art.”

The “Moon Museum” is the size of a SIM card, and Warhol had the idea of drawing… a penis on it. Why? Perhaps precisely because it is THE quintessence of popular art, the simplest, most visible, most represented, most absurd, and most daring… at a time when some US states still banned homosexuality? In the press, the NY Times censors the work with a thumbs down, stating that it hides “the artist’s signature…”

Nevertheless, this is the ultimate consecration for this clandestine penis tag: becoming a work of art for aliens. By simplifying its graphic form to the extreme, the phallus becomes a modern pictogram, a universal icon as in prehistoric times. The difference is that the penis now embodies the profane sacralization of our patriarchal society. We no longer worship sex because it is the source of the sacredness of life, but because it embodies the virile greatness of man, in an unacknowledged and secret cult. Because in the 21st century, the penis is most often censored.

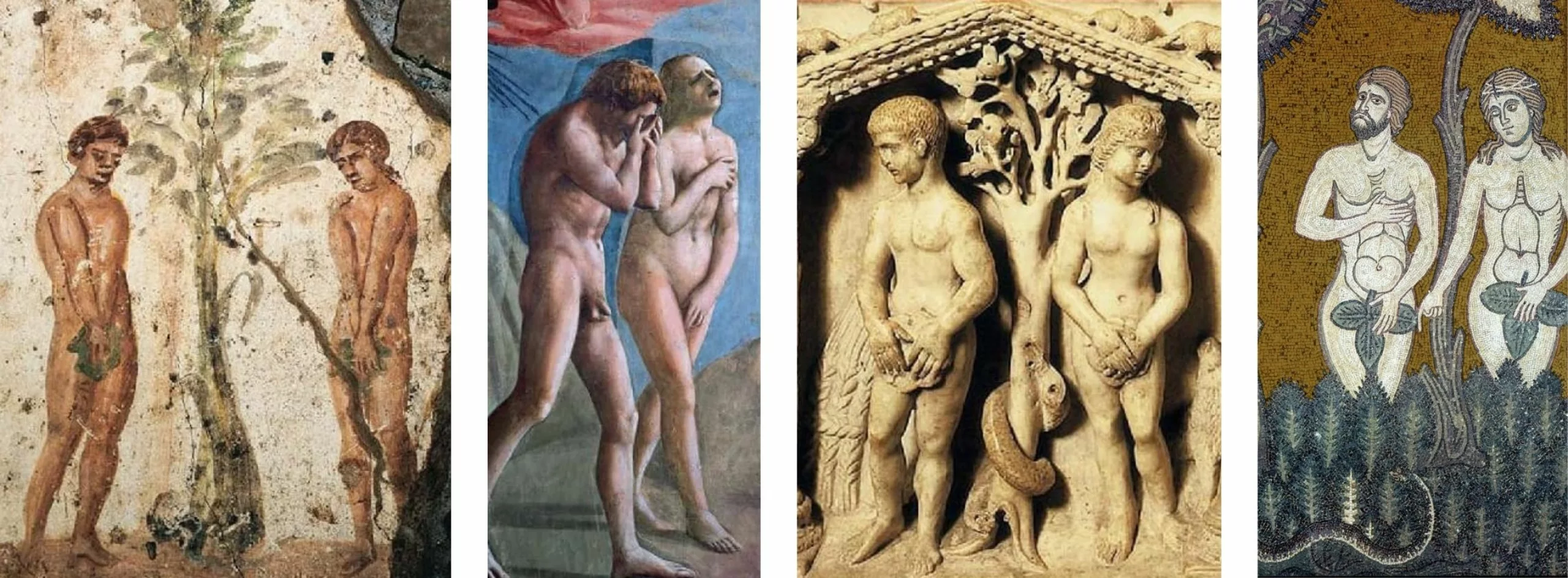

“Showcasing the penis kills sexuality.”

Perhaps to counter this trend, in 2015 designer Rick Owens had men walk the runway in clothes that revealed their genitals, thus reversing the principle of covering up. Did not Adam and Eve, ashamed, hide their private parts as soon as they were expelled from the Garden of Eden? A year later, Rory Parnell Mooney also revealed intimate areas such as nipples and belly buttons on the catwalk. But is revealing enough to trivialize and desacralize? Or, on the contrary, does framing these parts accentuate their profane sacralization?

By showing this, Owens exposes and forces the viewer to look at this area. He explains: “Nudity is one of the simplest and most primitive gestures; it has a powerful impact. It’s powerful.” And yet the Papuans of New Guinea, who live in their skins and couldn’t care less about Adam and Eve, use a penis sheath called a Koteka. But Owens’ fashion show does not highlight the primitive nudity of the Papuans, nor its power, since it carries no shame, no embarrassment, and has nothing to deconstruct or prove (unlike Western nudity). It is simply our discomfort that focuses on a piece of flesh laden with symbolism that we would like to deconstruct.

Is this gesture effective enough to desacralize the male sex? That is what Arnold van Geuns, another designer, thinks, believing that “by doing so, he (Owens) has killed, perhaps intentionally, sexuality.”

Whether it is a talisman in the Himalayas, risqué graffiti in Paris, or a medieval caricature, the penis stands out as one of the great absentees-present in our graphic culture. It appears where we least expect it, like the icon of a forbidden cult, a vanishing point in the visual order. It frightens, it makes us laugh, it makes us talk. Because the penis is a sign. It is written, represented, interpreted. And like any sign, it needs context, perspective, reinterpretation.

In our saturated visual culture, it is time to re-examine its place: not to censor it, nor to idealize it, but to understand it. The challenge is not so much to show it as to grasp what its representation, or its absence, says about us. The penis is a branding tool like any other, a phallic logo in the social alphabet. It belongs to the history of the image, and to its future. What if there were a representation of the penis other than as a symbol of power? Perhaps this is where tomorrow’s challenge lies: moving from the phallus drawn not to dominate, but to engage in dialogue. And not just thanks to eggplants.

Sources :

Claude Gaignebet, Art profane et religion populaire au Moyen Âge, Paris, PUF, 1985

Gil Bartholeyns, Pierre-Olivier Dittmar, Vincent Jolivet, Image et transgression au Moyen-Âge, PUF, 2008

Mikhaïl Bakhtine, L’Œuvre de François Rabelais

https://journals.openedition.org/mondesanciens/938

Joey Holder, I make dildos out of insect penises, Vice

Pourquoi les Grecs et les Romains vénéraient-ils le phallus ? The Conversation

Le phallus comme objet et véhicule d’humour dans la peinture de vases attique, Alexandre G Mitchel

Re-imaging Masculinity: The Sacred Masculine Archetype as Revealed in Four Cultural Artifacts, Smith, Drew Harrisson

Symboles phalliques

Le corps morcelé de Dionysos, Frédérique Ildefonce

Sex Symbols, Coline Sunier et Charles Mazé

conférence au Campus Fonderie de l’Image

Pour qui donc à Pompéi s’élevaient ces phallus ? — Le Monde