Mascots and virtual avatars in the digital age

This article is the third in a series about mascots, from their historical origins to their digital transformation. Find all the articles here:

- A history of mascots

- Brand mascots, from Bibendum to Bunny the Bull

- What strategies are hidden behind the mascots’ smile?

- Mascots and virtual avatars in the digital age

In the digital age: voice marketing and faceless mascots

Even though we still see physical mascots in commercials, the rise of digital technology marked a turning point in the mascot era around the mid-2010s. Since then, brands have created new “physical” mascots more and more rarely; today, they are more likely to be replaced by virtual avatars or even just voices. Tony was to ’90s cereal boxes what Miquela is to Instagram today. Mique-who? We’ll explain everything.

Voice marketing, when the mascot is nothing more than a voice

Since Clippy, Microsoft’s paperclip, virtual assistants have come a long way. Today, they do not even have a face anymore. Yet in our previous article, we explained how important it was for a mascot to show a smile, so that people could identify with it. But in the end, there is no need for a face to smile or create a connection. Speaking is enough. For nearly a decade now, brands like Apple, Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have been using increasingly advanced voice assistants, built into voice-controlled devices: Siri (2011), Alexa (2016), Google Assistant (2016), or the late Cortana (2014 to 2023), all of which allow customers to personalize their shopping experience or control their home.

Voicebots, voice robots, are a more “human” way to interact with these brands offering virtual services. Without the possibility of seeing the person who embodies the brand, you speak to them. Their voices have nothing robotic about them and are most often performed by humans: Cyril Mazzoti for Siri, Nina Rolle for Alexa, to make the exchange more realistic. Google even has, for example, an entire team responsible for creating the “personality” of its voice assistant, aiming “to be familiar without pretending to be human,” as explains Lauren Ducret, head of the French-language personality for the Google assistant.

In return, customers provide crucial data about their preferences and consumption habits, which brands use as a database to offer even more targeted and personalized marketing. In 2020, 20% of search engine queries were made by voice, and 77% of French consumers owned a voice assistant on a speaker or their phone, making voice commerce the fourth sales channel in France, mostly used by millennials or visually impaired people.

Personal intelligences and AI-powered voice assistants: the mascots of the future

Nevertheless, with the development of Artificial Intelligence, voice assistants already seem almost outdated in 2024 or on the verge of disappearing because brands are now developing “voice chat” solutions with integrated AI. This combination draws information from users’ emails, photos, and data to assist them daily, but can also process or summarize text, and even create visuals.

At the end of 2023, Humane revolutionized the smartphone world with the AI pin, a magnetically attached AI-connected device without a screen, functioning as a “personal assistant and second brain” whose name “Humane” emphasizes the company’s desire to reconnect with real life without being cut off by a screen. A few days earlier, Microsoft had officially launched Microsoft 365 Copilot, which, combined with the Word, PowerPoint, Excel, and Teams suite, “works by your side.” Very recently, Apple announced the upcoming update of Siri combined with OpenAI’s ChatGPT by creating the “personal intelligence” Apple Intelligence, which understands spoken language errors and written text. The French company Kyutai has just overtaken OpenAI by launching Moshi, a voice assistant (still a prototype, currently only speaking English) that responds in real time, even interrupting, whispering, reproducing emotions, and can clone the voice of the person speaking to it: a first in the field. Amazon is developing Olympus, which promises to be twice as powerful as GPT-4 and soon integrated into Alexa.

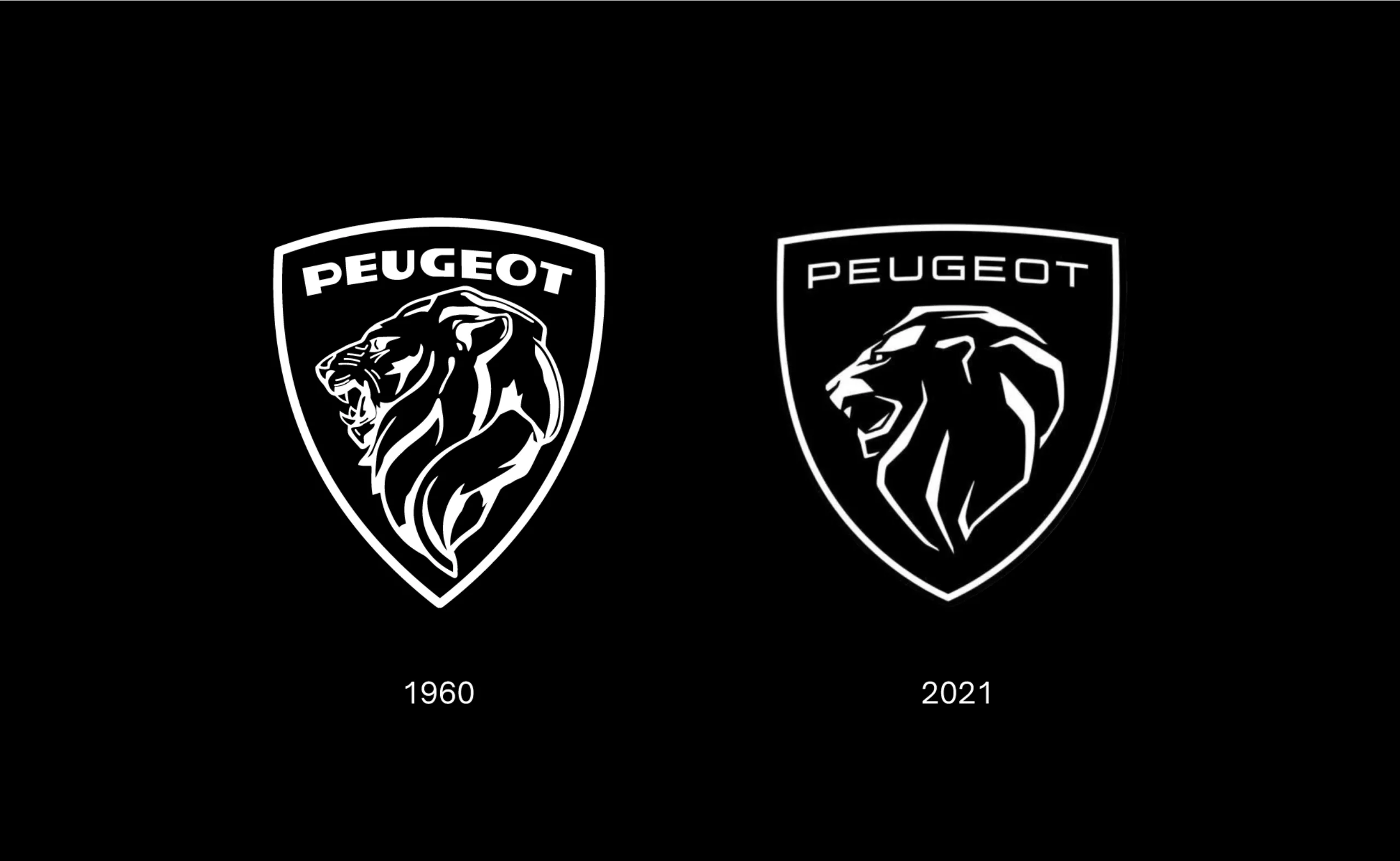

Now, the assistant is in our pocket, organizing, correcting, teaching, and creating, blurring the lines between private life, work, and our relationships with the outside world. Visually, they have no physical form (except for the hybrid AI-pin, which is partly a connected device), and their representation, when it is not a logo like Copilot365, is reduced to a glowing dot or a simple light. This is the case for Moshi, Siri, which is nothing more than a color fluctuation displayed at the edges of the screen, or AI-pin, which lights up when connected. This glowing dot is a tribute to the red dot of Hal 9000, the voice assistant from the futuristic film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

Becoming God and Creating Avatars

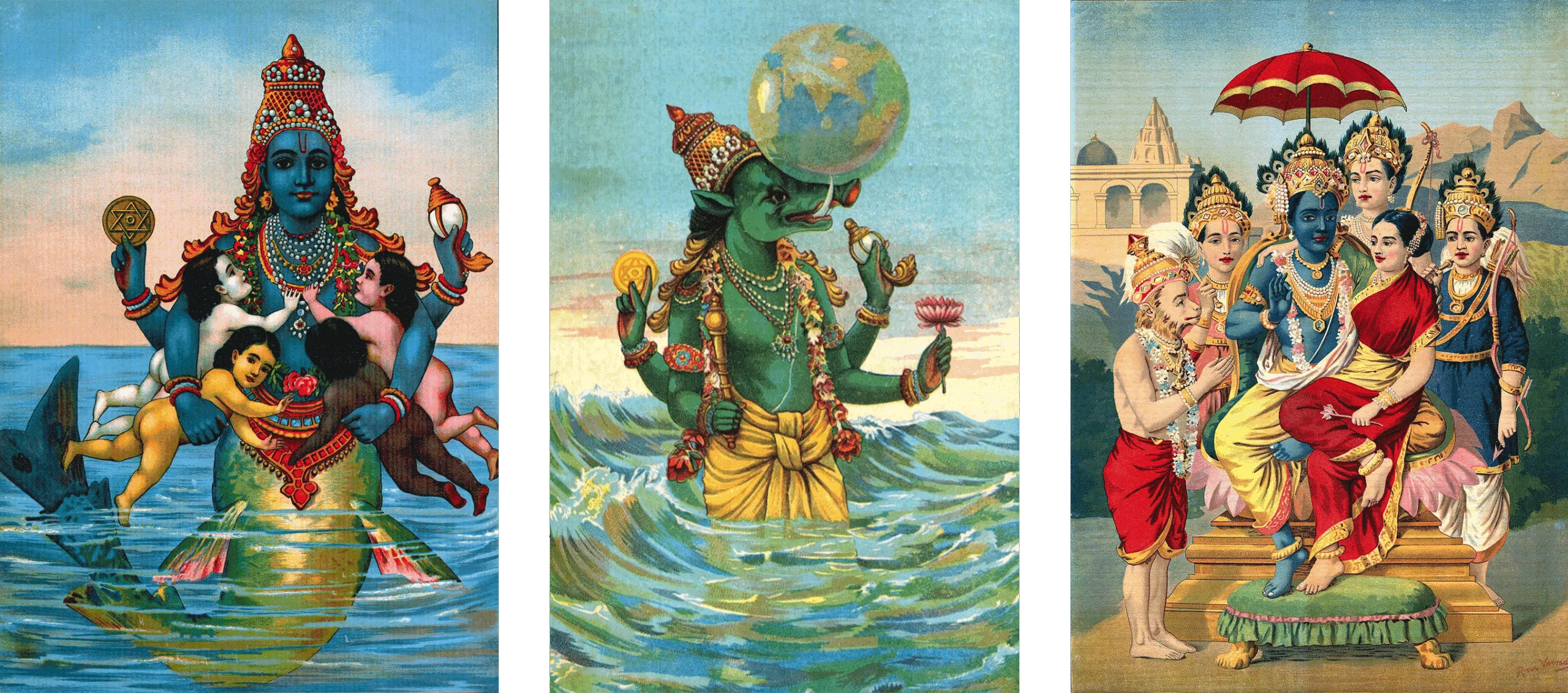

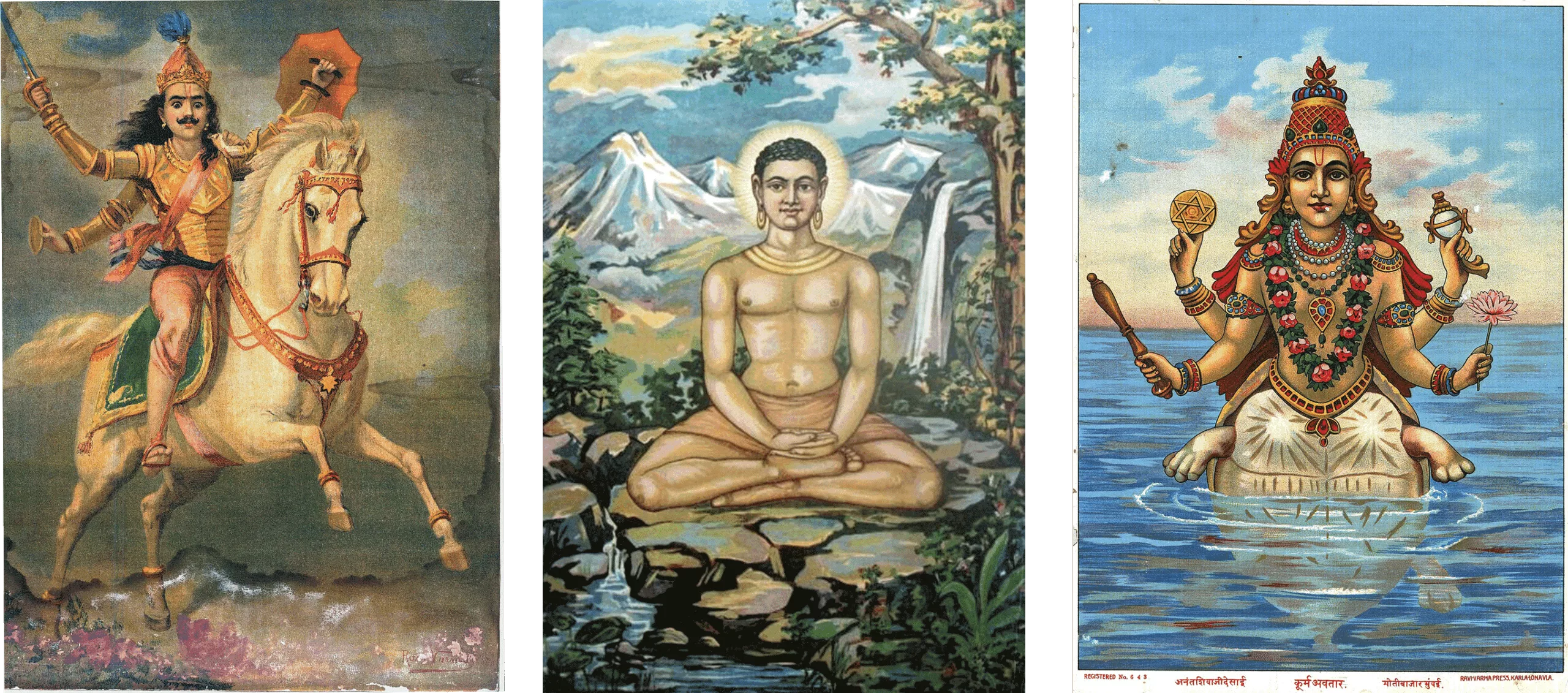

Mais les mascottes n’ont pas disparu pour autant, elles se sont juste désincarnées pour certaines, en devenant des avatars, des projections. L’avatar est un moyen de transposer un corps dans une autre forme qui le représente, pour avoir d’autres interactions sociales. Pourtant, si le terme vient du sanskrit “avatâra“, descente, qui symbolise l’incarnation d’une divinité Hindou sur Terre, pour les mascottes, le processus est inversé : elles quittent leurs “corps” de peluche pour devenir des sortes d’esprits virtuels et immatériels. Plutôt comme un hologramme !

But mascots have not disappeared; some have simply become disembodied by turning into avatars, projections. An avatar is a way to transpose a body into another form that represents it, allowing for different social interactions. Yet, although the term comes from the Sanskrit “avatâra,” descent, which symbolizes the incarnation of a Hindu deity on Earth, for mascots the process is reversed: they leave their plush “bodies” to become kinds of virtual and immaterial spirits. More like a hologram!

Unlike robotic voices but still within this digital assistance trend, more and more brands are developing such humanoid and virtual assistants to enhance the user experience, the “human digital ambassadors.” This is called a “phygital” experience (physical plus digital; in French, one might say “phymérique“), where the boundaries between physical and digital are blurred, and the consumer integrates digital features into their real-world experience. QR codes, screens with assistants, or digital ordering counters are all examples of phygital experiences.

Some stores offer digital product try-ons, like Nike NY with personalized shoes, or Sephora, which lets customers try makeup in a virtual salon. Qatar Airways recently introduced its assistant Sama 2.0 connected to AI (created by the agency Uneeq Digital Humans), the first virtual flight attendant. In cosmetics, Kiehl’s Eve assists customers in stores via iPad.

The company MagicLeap, for its part, has developed a prototype, Mica, who can look her interlocutors in the eyes thanks to AI, and has the advantage of having facial expressions, body language, and postures far more realistic than most commercial avatars, eliciting reactions and genuine nonverbal communication with users.

Here, we are no longer talking about robots, mascots, or avatars, but about digital humans, emphasizing the promise of realism more lifelike than nature itself, like Galatea from the myth of Pygmalion, in version 3.0: without flesh or bones!

The invention of “marketing” avatars is not new; one notable example is the band Gorillaz, which brought to life a virtual group (with real musicians and singers) for over 20 years. Unlike Sama and Eve, these characters do not aim to be a perfect version of humanity but represent diversity and each have their own personality.

From Liv to Reno, Renault’s experiments with humanized avatars

In 2019, Renault created Liv to promote the Kadjar in an advertisement produced by Publicis Worldwide. Liv was an avatar who immersed herself in reality and experienced intense emotions, inviting humans to do the same.

One may question the relevance of using a robot to promote a very real car and, above all, to evoke positive emotions. Beyond the surprise effect and the innovation it represented at the time (before generative AI and Covid), it is mainly Liv’s strange appearance that makes us hesitate and pull back today: Liv is too human to look like a robot, yet seems too unusual to inspire attachment.

In 2022, Renault ultimately chose to launch Reno, a virtual and smiling mascot offered as an assistant in the brand’s electric vehicles: a blue and yellow diamond with floating hands and a pixelated screen face. Arnaud Belloni, Renault’s marketing director, sees it as a “humanized avatar,” but its retro look is more reminiscent of the good old Clippy than other existing humanoid mascots. Reno nevertheless has the advantage of being “friendly” like those good old plush mascots, even if it already seems outdated before its time, especially behind the wheel of electric vehicles. Finally, retro is in fashion, so why not? One can imagine that it is the result of a cautious strategy aimed more at avoiding discomfort by offering a human avatar that is not sufficiently perfected… as was the case with Liv.

Eve of modern times

It is interesting to note that most of these humanoid creatures are female figures, kinds of modern Eves or Venuses, embodying the promise of pure and perfect beings, mothers of future avatars to come, created by humans now equal to God. The fear of daring to take God’s place, which once terrified Westerners at the time of the first automata (discussed in the first article), now seems distant and forgotten. On the contrary, this creative power is openly claimed and embraced! The names of the assistants and their genders say a lot, from the very implicit “Eve” to “Sama,” which means “sky” or “paradise” in Arabic, and even “elevation.” The name “Mica,” of Hebrew origin, means “who is like God.” Finally, “Liv” evokes the English word “live,” meaning to live.

These figures are pure creations with human form but destined to be divine, whose humanity, more than perfect, aims to unsettle us, like Samantha in the film Her, or the new creatures generated today with AI.

Virtual influencers, more powerful than avatars

To take the experience even further, some brands now call upon virtual influencers, mostly created by the creative studio Virtual Humans. Their profiles, verified by Instagram, have thousands or even millions of followers, just like real people. Created experimentally, they now engage their audiences three times more than humans do! These virtual icons share their daily lives, tastes, and values online, creating attachment with a certain audience who identifies with them.

Brands see this as a huge and innovative marketing opportunity to reach this target audience, since collaborations with virtual spokespeople are still rare, and they pay substantial sums to promote their content in “partnership” with various virtual personalities. The advantage for these brands is that these modern icons never age, always look flawless along with their lifestyles, can exist 24/7, speak multiple languages, and will never cause scandals: no body means no sex or drugs. In China, for example, many (human) social media stars are suppressed by the government, which deems them immoral or vulgar according to its moral standards. Poor Britney nearly lost her \$108 million Pepsi contract after being caught by paparazzi holding a Coke in 2001.

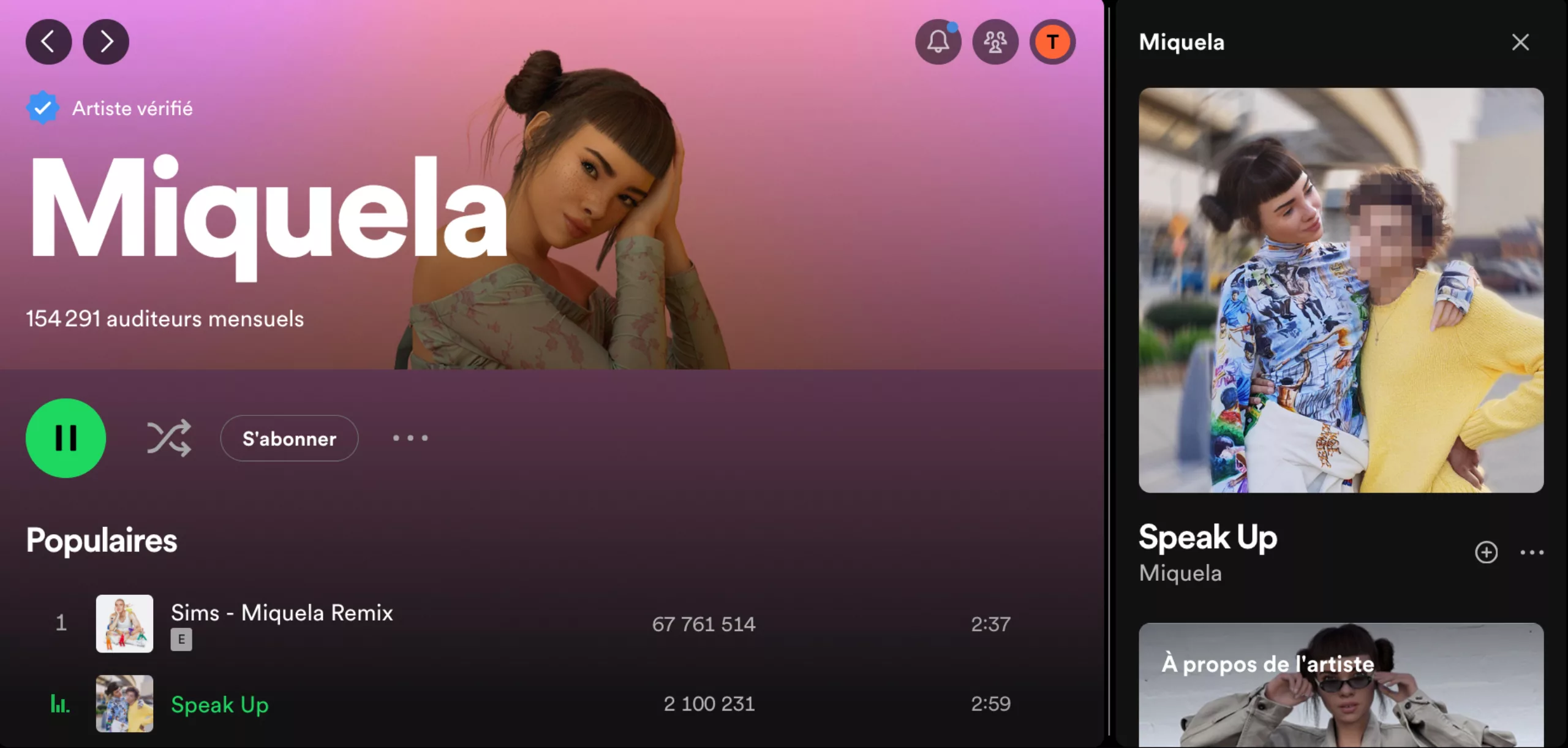

Lu, Imma, the funny sausage, and Miquela

The most followed virtual influencer in the world is Brazilian, yet she is known only there. Lu do Magalu is the mascot and spokesperson for the Luisa stores of the huge Brazilian group Magalu, which owns numerous shops selling gadgets and household appliances. With 6.8 million followers on Instagram and 33 million across all platforms, she has “embodied” customer relations since 2009 (initially on YouTube, but also on the brand’s website and the group’s mobile apps). There, she offers practical advice by “using” products from the real stores she promotes on her Instagram account, and she even created her own line of lipstick. Lu has posed for Vogue and Elle Brazil, and regularly engages in commercial collaborations. Yet, she looks more like a character from The Sims than a real woman.

In the top two most followed virtual influencers in the world, we find… a sausage with hair as fabulous as its booty shake: Nobodysausage. Sometimes feminine, sometimes masculine, it turns ordinary everyday scenes into humorous sketches inspired by real human news stories. Brands jumped at the opportunity to reach its 7.8 million followers, and it was recently seen collaborating with Sephora and Hugo Boss.

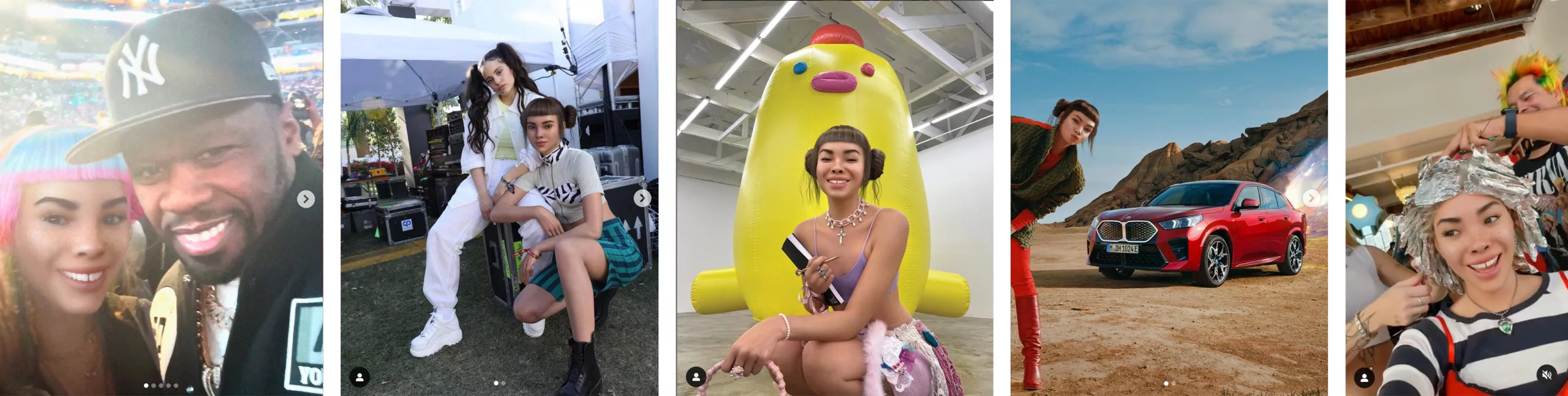

Finally, Brazilian-American Lil Miquela, forever 19 since 2016 (with 2.5 million followers on Instagram), is THE virtual influencer based in Los Angeles. She sings (she has her own Spotify account), participates in fashion week shows, models for Dior, Chanel, Porsche, Burberry, and many luxury brands, as well as BMW, Calvin Klein, and Ugg, and promotes the Samsung Galaxy, of which she is part of the “team.” Miquela takes part in basketball games, gets her hair dyed in salons, and poses with Rosalía or Bella Hadid. Her face is superimposed onto the body of a real human, blurring the lines between real and virtual. The virtual teenager charges \$10,000 per Instagram post, and her partnership with Samsung cost over \$10 million. “Miquela claims to be an AI robot. A fictional entity acting like a human being, manifesting as a robot in flesh and blood.”

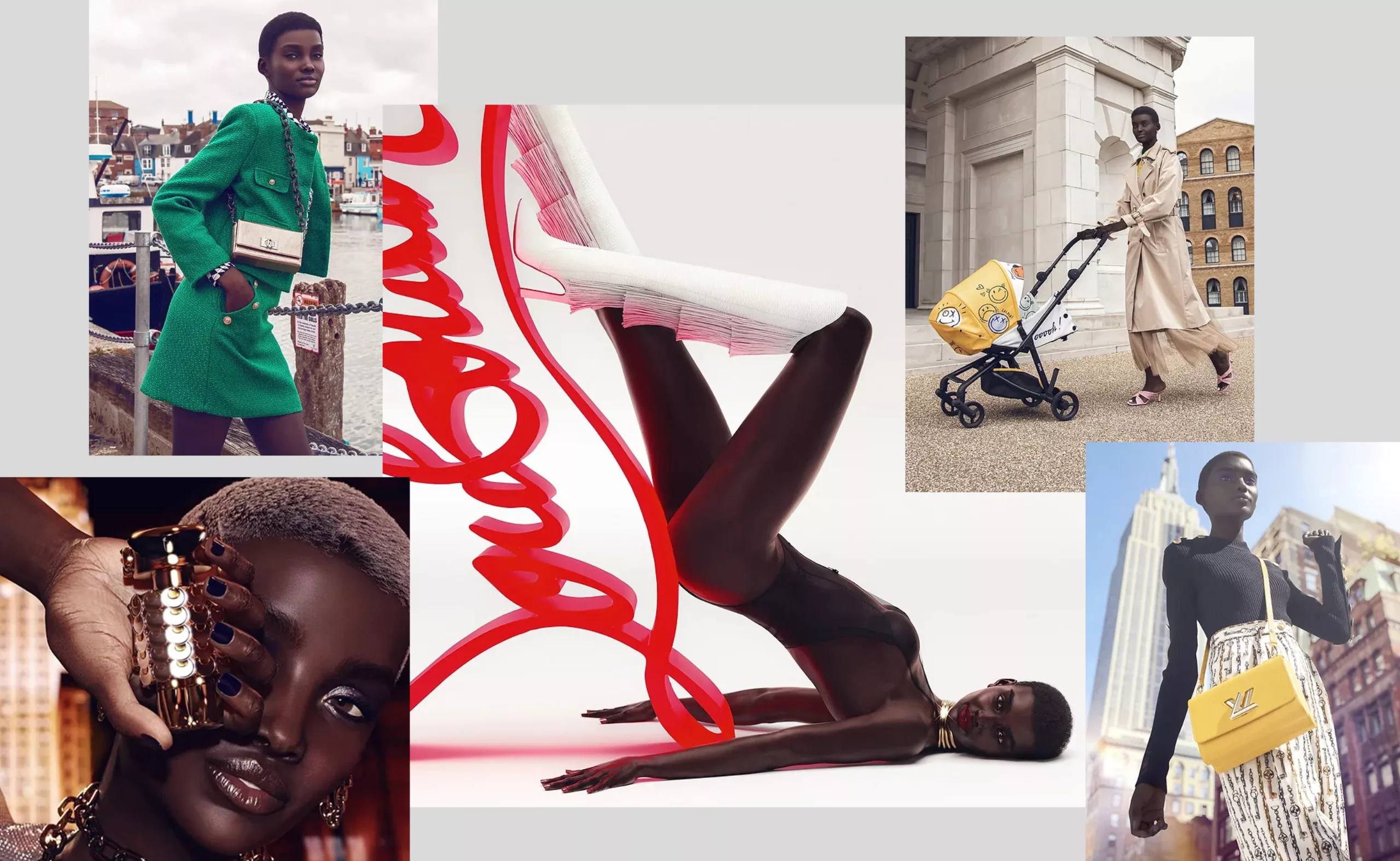

The fashion industry also has its virtual spokesmodels, such as Shudu, the first digital supermodel from the agency The Diigitals. In 2018, the agency also created a “virtual army” of three models for Balmain. These spokesmodels pose for various brands, from Louboutin to Smart. In Japan, it is Imma, created in 2018, who promotes both virtual and real brands. She has a family and a dog, and in 2020 she spent three days in an IKEA show apartment, where you could see her vacuuming, getting her nails done, scrolling on Instagram, or watching movies. Real life, basically. Her hyper-realistic and detailed modeling makes her a character easily mistaken for a real woman.

The limits of humanoid avatars: too human to be human?

If these spokesmodels and avatars are likely the future of brands and mascots, the fine line between reality and fiction in humanoids can quickly shift from empathetic fascination to repulsive discomfort. The more human they seem, the more familiar they become to us… but it only takes one oddity to trigger the opposite: unease, a feeling of rejection, plunging us into what Masahiro Mori called the “uncanny valley” (1970), which Denis Vidal describes as the “anthropomorphic trap,” when we realize we have been deceived. So, it is better to boldly declare from the start that the creature is not real. Traditional mascots at least had the advantage of not appearing real.

Because very simple machines like puppets with coarse features, furry smiling mascots, or automatons with visible mechanisms (like the Machines of the Isle in Nantes) are enough to create the fascination of the living and generate empathy… so why insist on creating humans more human than humans? It is probably because it finally allows us to play God, after so many centuries of taboos… Carried away by the vertigo of shaping a perfect creature according to our own aesthetic criteria, only technology can restrain our passions. But for how many more days?

To go further :

Histoire des automates : animaux et humanoïdes

Robots étrangement humains

D’où viennent les mascottes ?

An explaination of virtual influencers and realness