The raised fist: symbol of fight and protest

The raised fist is a symbol of struggle, revolt, and resistance worldwide. While it was recently seen raised in support of the #BlackLivesMatter movement against police violence against African Americans, the history of the raised fist is the legacy of two entire centuries of struggle. From the streets of Weimar to the Olympic podiums, from communist posters to Black Panther newspapers, via Heartfield and Mandela, the clenched fist stands tall as a sign of unity and activism.

Revolution as its root, art as its medium

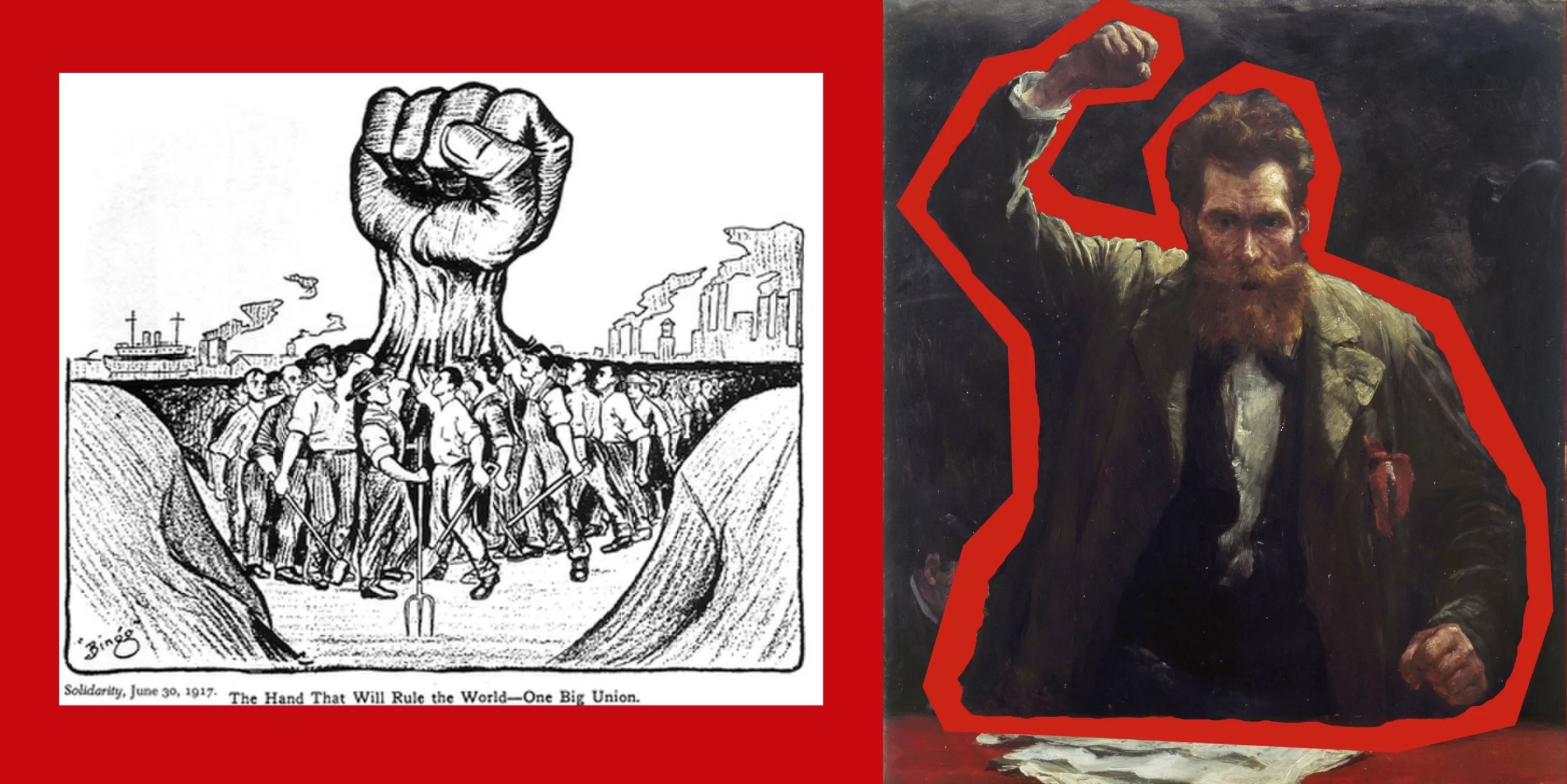

While today the fist is raised mainly for the social rights of minorities, it has its roots in the French Revolution. Not that of 1789, but that of 1848 (painted by Honoré Daumier in the same year, see illustration below), which laid the foundations for socialism, as Alexis de Toqueville explained at the time: “the people alone bore arms. (…) Specific measures were proposed to combat poverty and remedy the evil of labor, which has tormented humanity since its inception. All these theories (…) took the common name of SOCIALISM.”

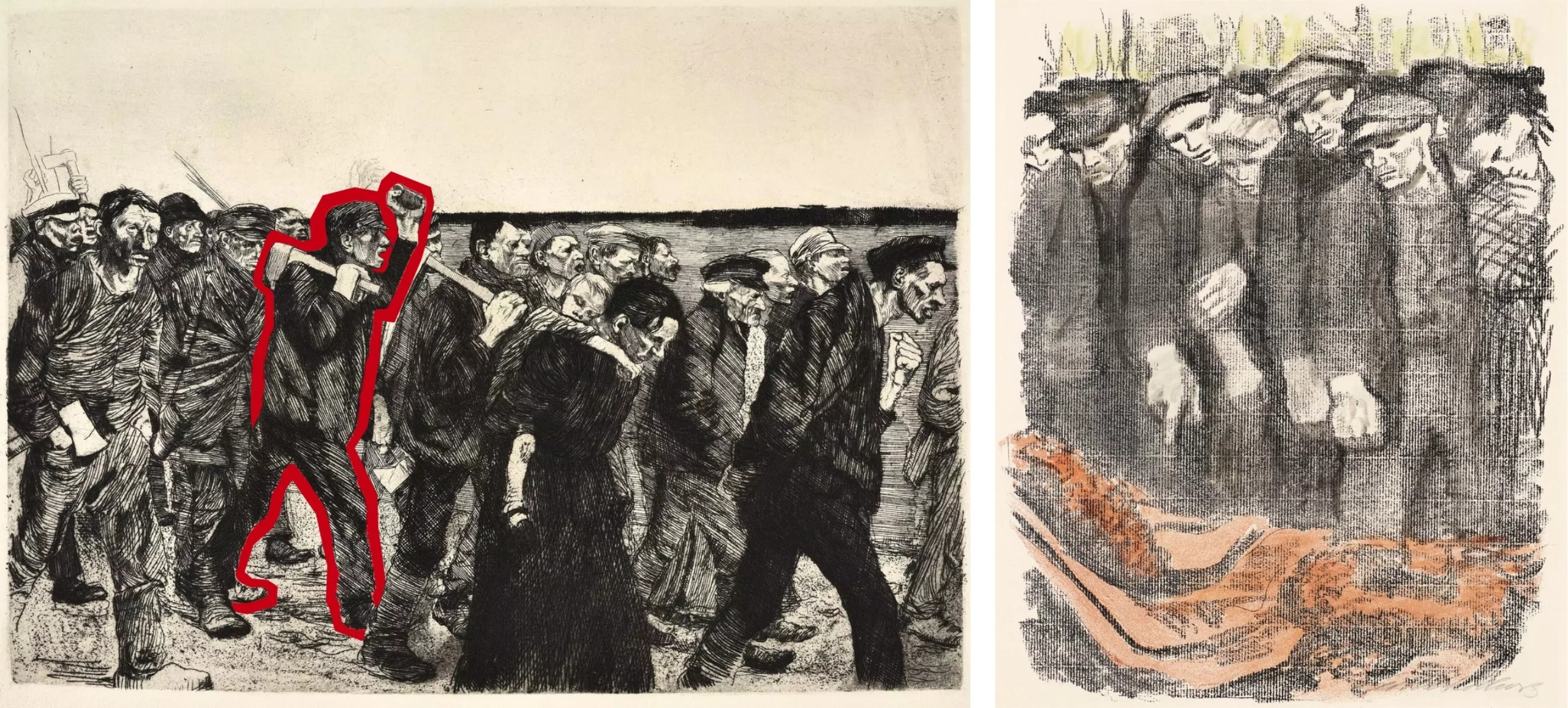

In 1885, German painter Robert Koehler painted “The Socialist” with both fists clenched, ready to fight and bang his fist on the table. The iconic image of the socialist with his fist raised symbolizes the warrior-like determination and underlying violence of a people ready to explode.

But even before being depicted on canvas, the raised fist already contained the philosophical idea at the origin of 19th-century socialist thought: the hand as a metonymy for the worker. It was the Marxist Friedrich Engels who, in 1876 in The Part Played by Labor in the Transition from Ape to Man, positioned the hand as both the organ and the product of labor.

This essential tool, which shaped humanity by distinguishing it from primates, has since come to embody the very symbol of productive force in the working-class imagination. This symbolism has almost never left this gesture.

American trade unionist William “Big Bill” Haywood developed another metaphor, comparing the fingers of the hand to workers. During the silk strike in 1913, he said: “Individually, fingers have no strength,” but once clenched…

Red and Black, rituals and raised fists

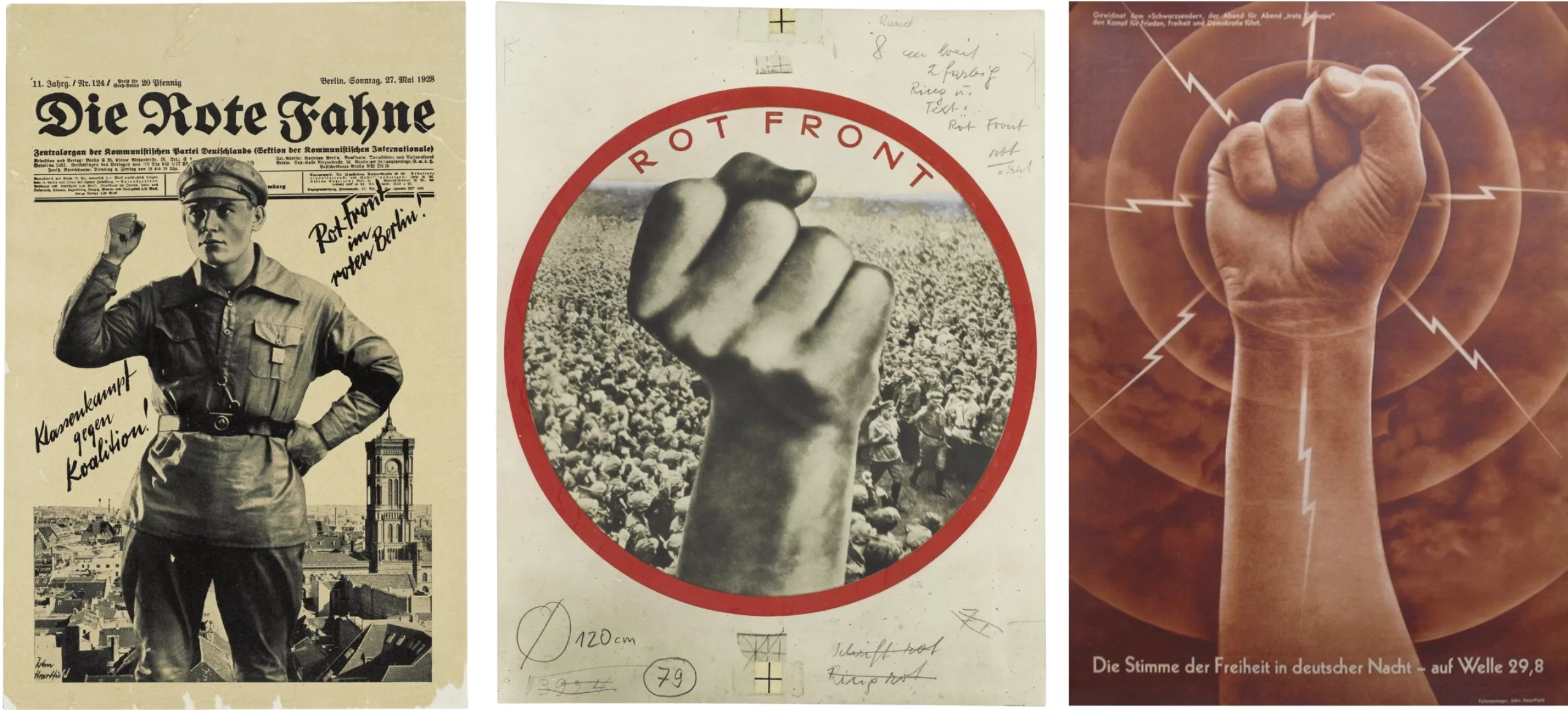

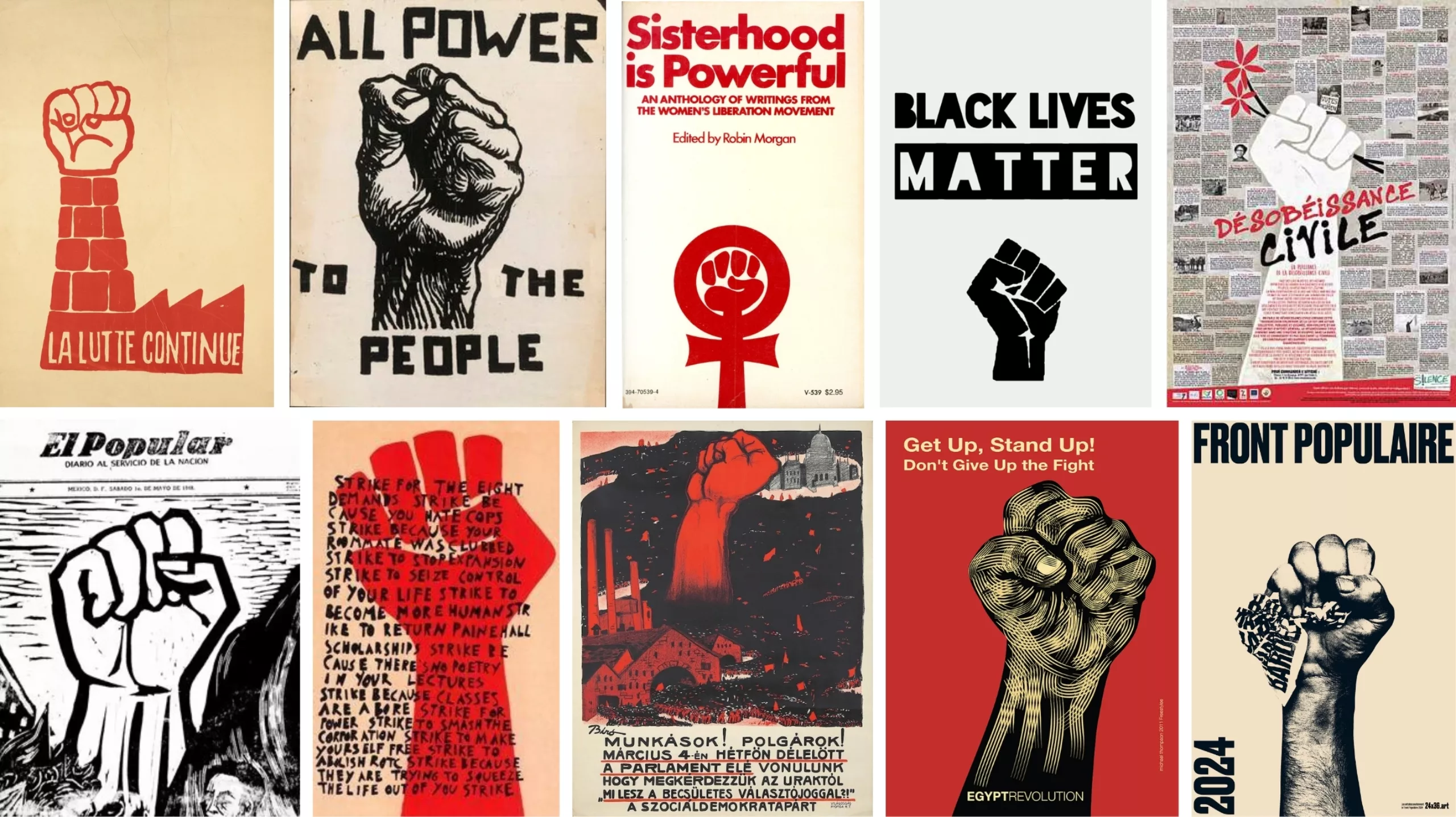

But the history of the fist really began in Weimar Germany. In the mid-1920s, John Heartfield (one of the great names in the history of graphic design), a satirical graphic designer committed to fighting the rise of Nazism and supporting the German Communist Party, created the logo for the Rot Front (Red Front). It features a monumental raised fist encircled in red against a backdrop of a crowd, in a photo collage (Heartfield’s favorite technique). The party newspaper, Die Rote Fahne (The Red Flag), contributed greatly to the spread of the anti-fascist model and the militant “red” worker in his shirt with a raised collar.

The culture of kampf, a mirror against Nazism

The clenched fist at the end of an outstretched arm is a gesture derived from a strictly regulated combat ritual, kampf (combat), propagated by the militia of communist fighters, accompanied by a cry of “Rotfront!” (red front), uniforms, parades… all within a culture of war. This figure of the combative militant contrasts with the classic attire of city men, where the hat is swapped for a Lenin cap, and the shirt and tie for a scruffy jacket with a Mao collar. The party was banned in 1929, but the figure of struggle persisted.

As Gilles Vergnon explains in Le “poing levé” (The “raised fist”), from soldierly ritual to mass ritual, the figure of the Communist militant is compared to that of the Hitler Youth: this culture of kampf echoes the nascent rituals of Nazism in the common goal of forming an army, even if the fight is not the same… To symbolize the union of the left against the rise of fascism, the clenched fist was chosen as the inverse mirror of the Nazi Roman salute. The political symbol shifted from the guiding hand to the hand that strikes or threatens to strike.

Two symbols, two clans, two outstretched arms, but one hand clenched, the other open. As the fight against the rise of the far right intensified at the dawn of World War II, fists were raised in Europe in the face of outstretched palms, as here in England.

Raising fists to unite and recognize each other

The image of activists raising their fists also reappeared in France in the 1930s, among the working class. Photographers immortalized groups of strikers, united, fists raised, united by this now iconic pose (most often men, workers), chanting the Internationale. The gesture was rather good-natured, as Gilles Vergnon explains, even if anger remained.

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), the gesture became the “anti-fascist salute,” brandished by Republicans and accompanied by the cry “¡No pasarán!” (they shall not pass), the political slogan of the committed (Stalinist) communist Dolores Ibárruri, which she borrowed from the soldiers in the trenches.

Comradeship led other international brigades to join forces, recognizable by their clenched fists and banners, which broke down language barriers through sheer force. The fist became “the emblem of a merciless struggle (…) through the prism of the clash between fascism and anti-fascism.” A letter from the Spanish Civil War adds: “…it signifies the life and freedom for which we are fighting and a salute of solidarity with the democratic peoples of the world.”

The proletarian revolution spread throughout the world: in Laos, China, Vietnam, Russia, during the Cuban Revolution, and mainly in communist countries.

The raised fist in the United States, a Black Power icon of African-American civil rights movements

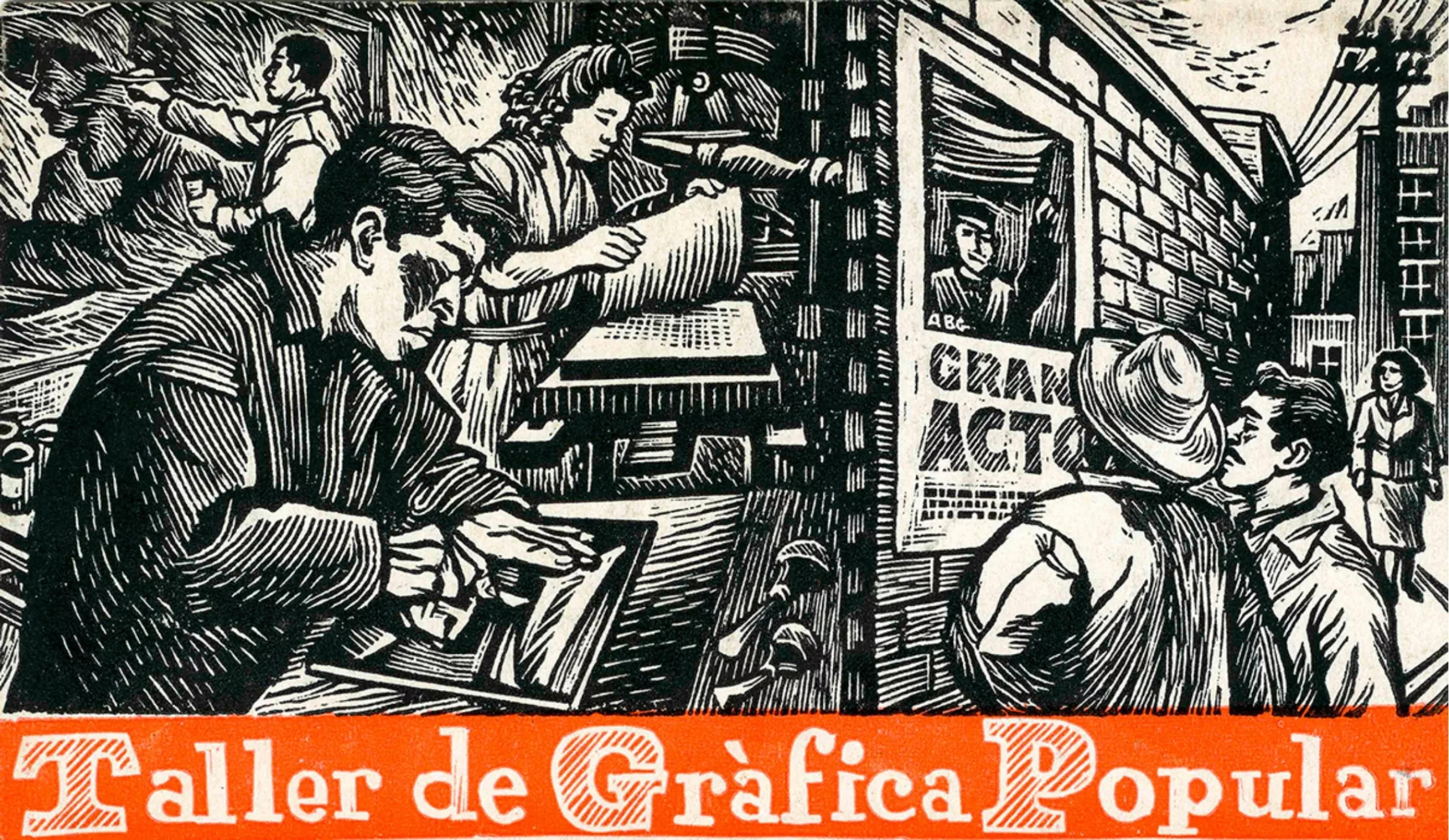

The struggle continued across the Atlantic in the Mexican popular graphic workshops (Taller de Gráfica Popular) in the late 1940s, which used art to promote revolutionary social causes. The fist then arrived in the United States. The icon came to serve black populations fighting for their rights against racism and police violence.

In 1964, American artist and volunteer activist Frank Cieciorka created a stylized woodcut of the clenched fist symbol for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which was later adopted by the Black Power organization. The design is deliberately simple, with few lines, so that it can be easily reproduced on badges or with stencils, becoming a pragmatic and effective tool for mobilizing student activists.

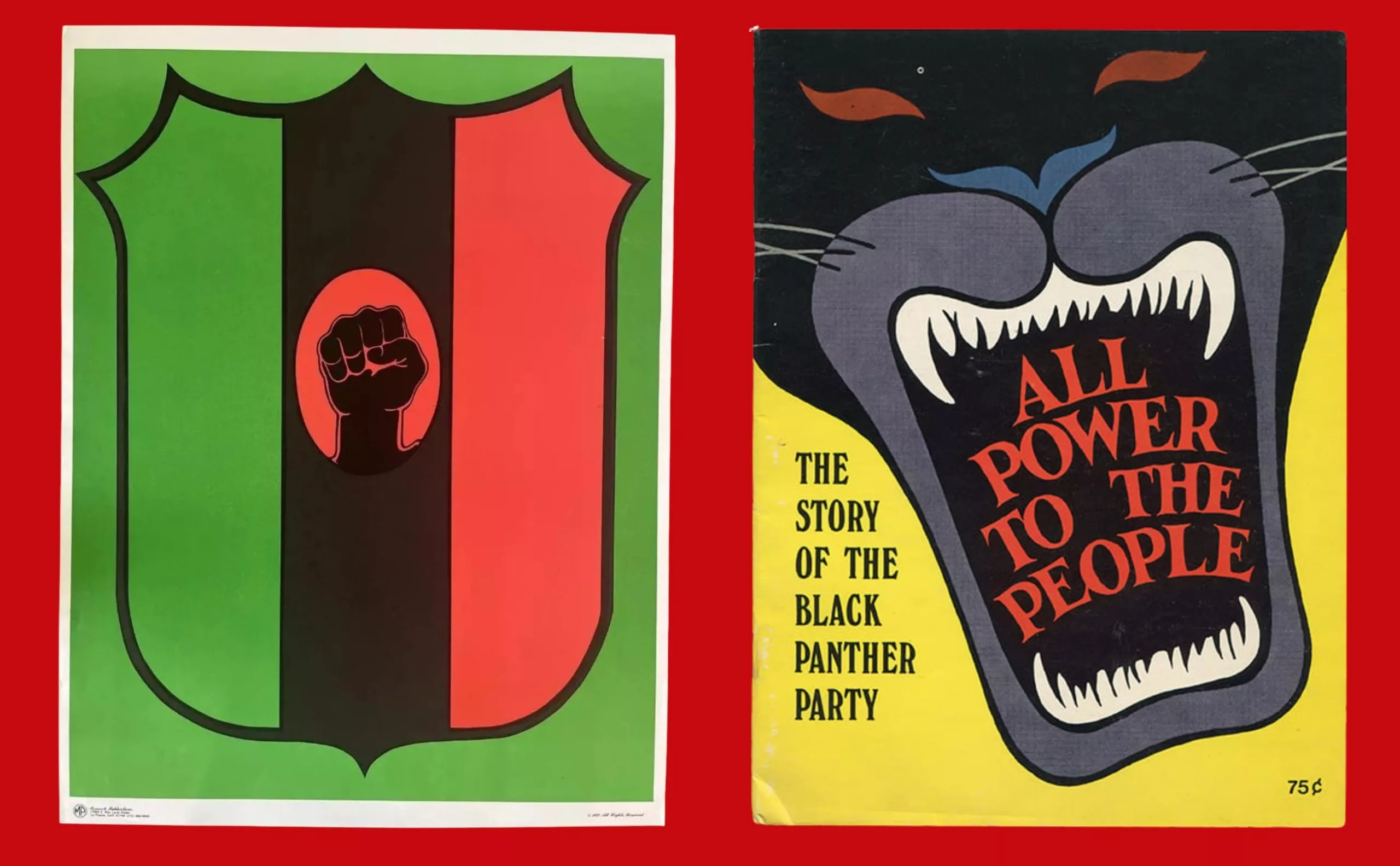

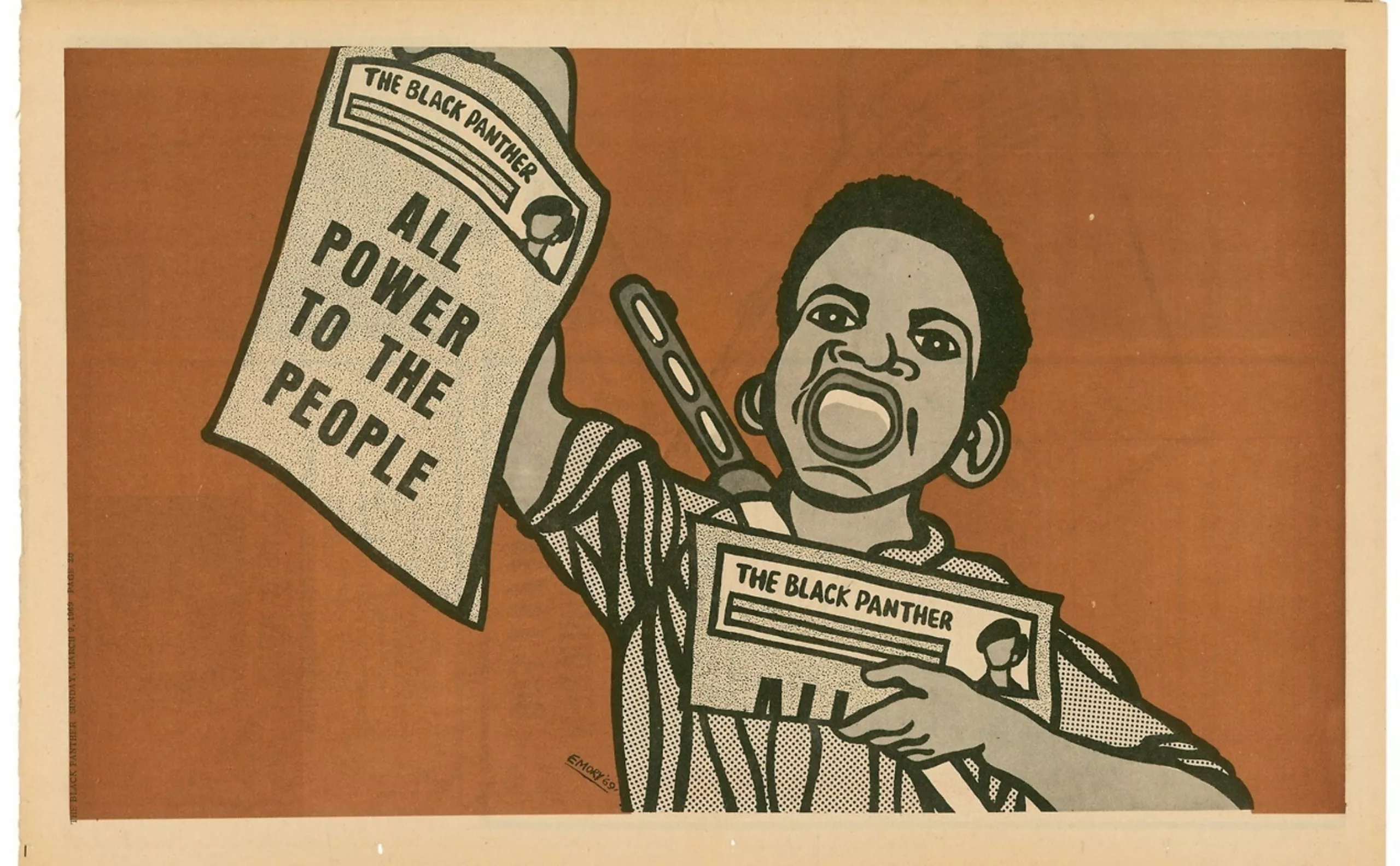

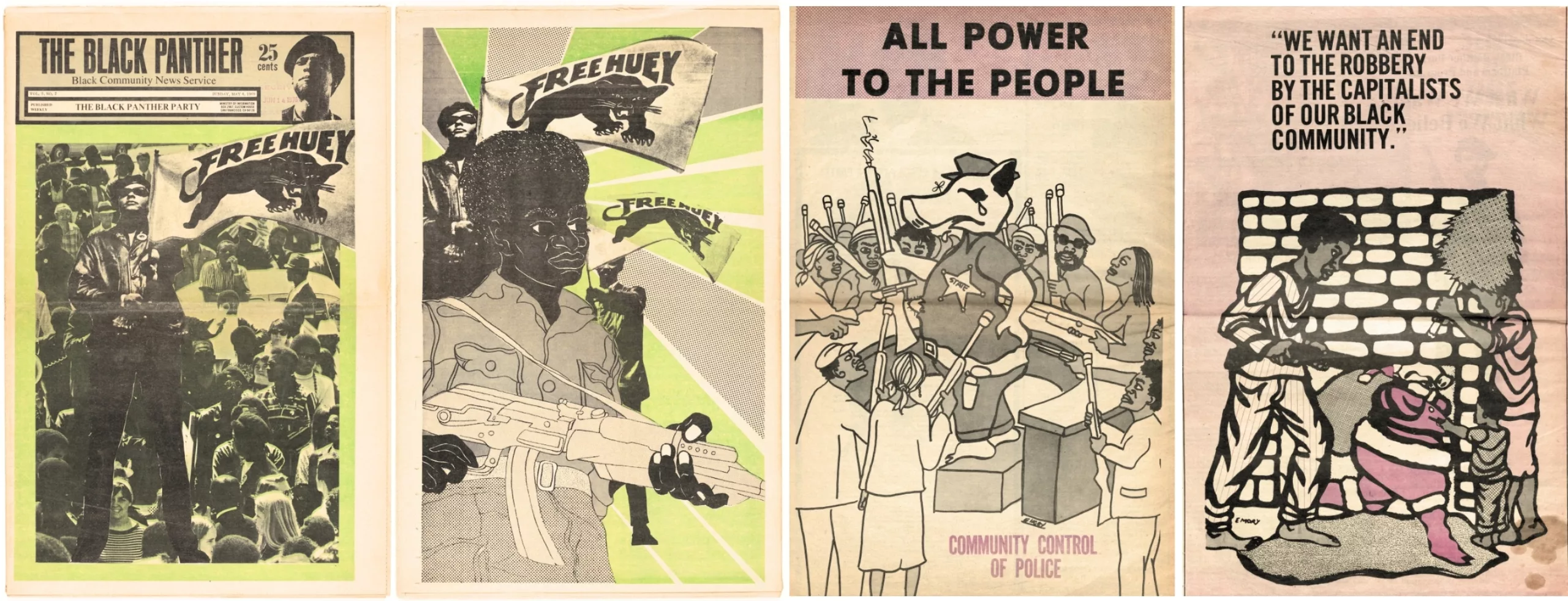

The Black Panther Party and Emory Douglas’ style

At the same time, Emory Douglas, graphic designer for the Black Panther Party (founded in 1966), made the clenched fist a pillar of the movement’s communication in the pages of the party’s newspaper, The Black Panther. The goal was crucial: at a time when much of their audience was illiterate, visual communication was essential.

The raised fist spoke where words could not. It conveyed a message of strength, unity, and resistance that required no literacy, only a shared awareness of the struggle. It should be noted, however, that “all the major Black Power organizations were either openly socialist or communist, or inspired by socialist or communist ideas.” Hence the gesture. (This is partly what led to their demise, in the midst of the Cold War, due to pressure from the FBI, which was hunting down communists.)

E. Douglas works with large capital letters, strong visuals in drawings or collages in which oppressors (white police officers) are represented by pigs, and only one or two colors in addition to black. Fascinated by the look of woodblock printing, he recreates the effect and textures in his own way (and without wood) to save time, using markers, pens, ink, and other materials.

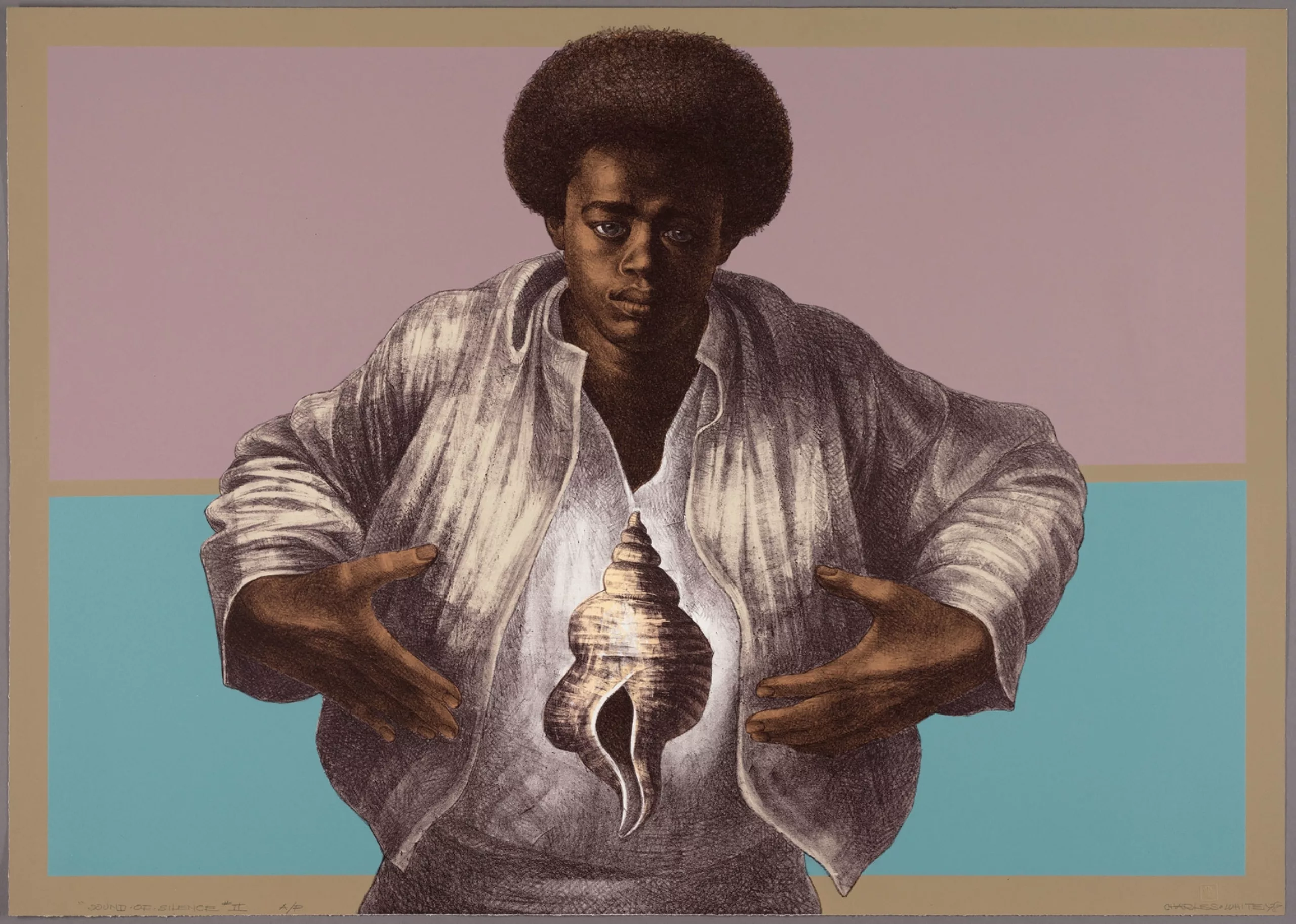

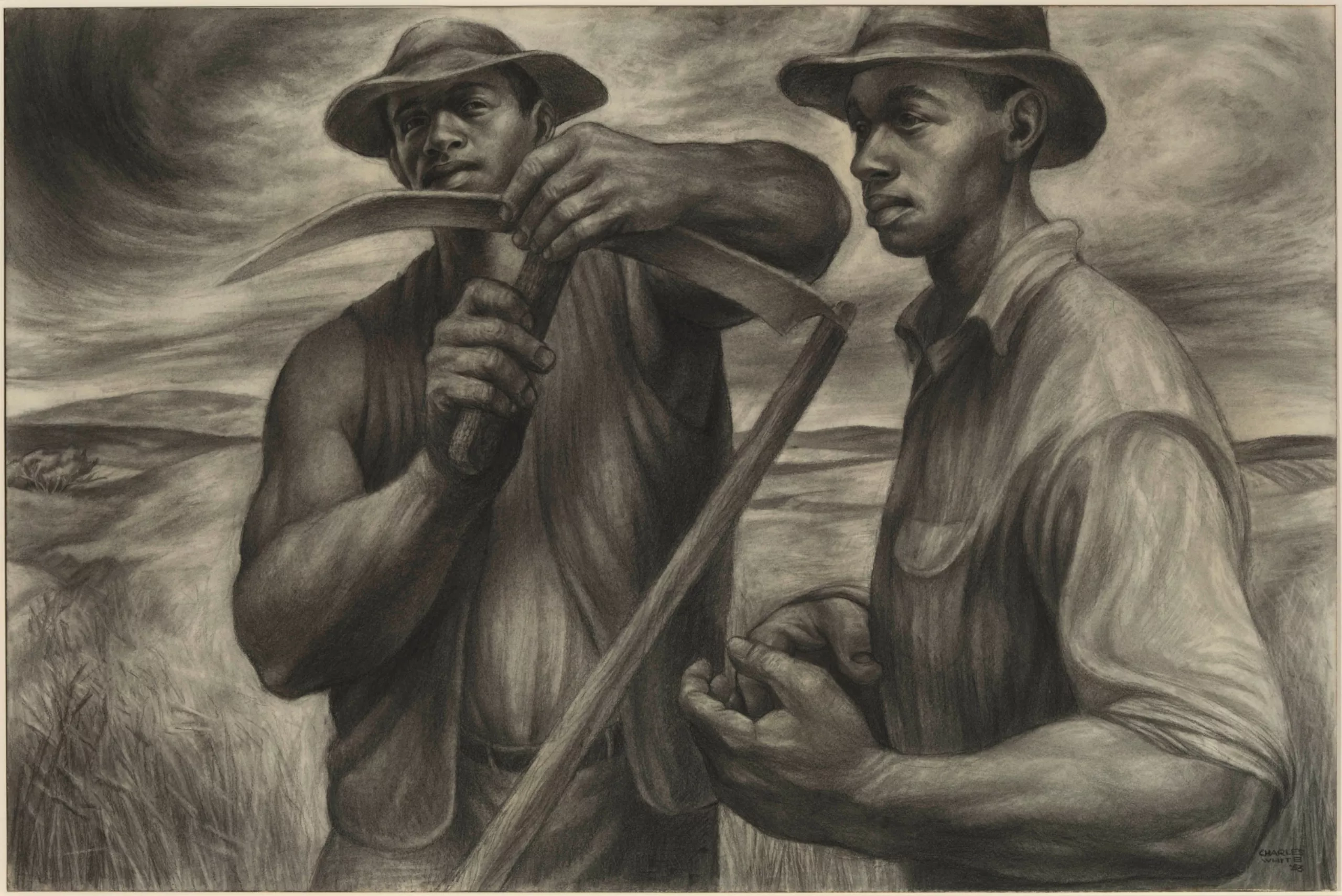

His work is inspired by John Heartfield‘s collages, woodcuts from the Mexican popular graphic workshop, and the engraver Käthe Kollwitz, whose poignant works depict the daily struggles of workers. Douglas’s works feature the symbolic elements of Black Power: the Afro hairstyle, leather jacket, clenched fist, weapons, sunglasses, and beret.

Emory Douglas also draws on and passes on the legacy of African American artists such as Aaron Douglas‘s emancipated silhouettes, Charles White‘s realistic drawings, and Romare Bearden‘s collages, which celebrate African American culture and African pride. His front-page illustrations are very popular and are often reprinted as posters and displayed in the streets or at demonstrations. Douglas explains that “people saw themselves in the artwork. They became the heroes. They could see their uncles in it. They could see their fathers or their brothers in the art.”

A symbol of social struggles

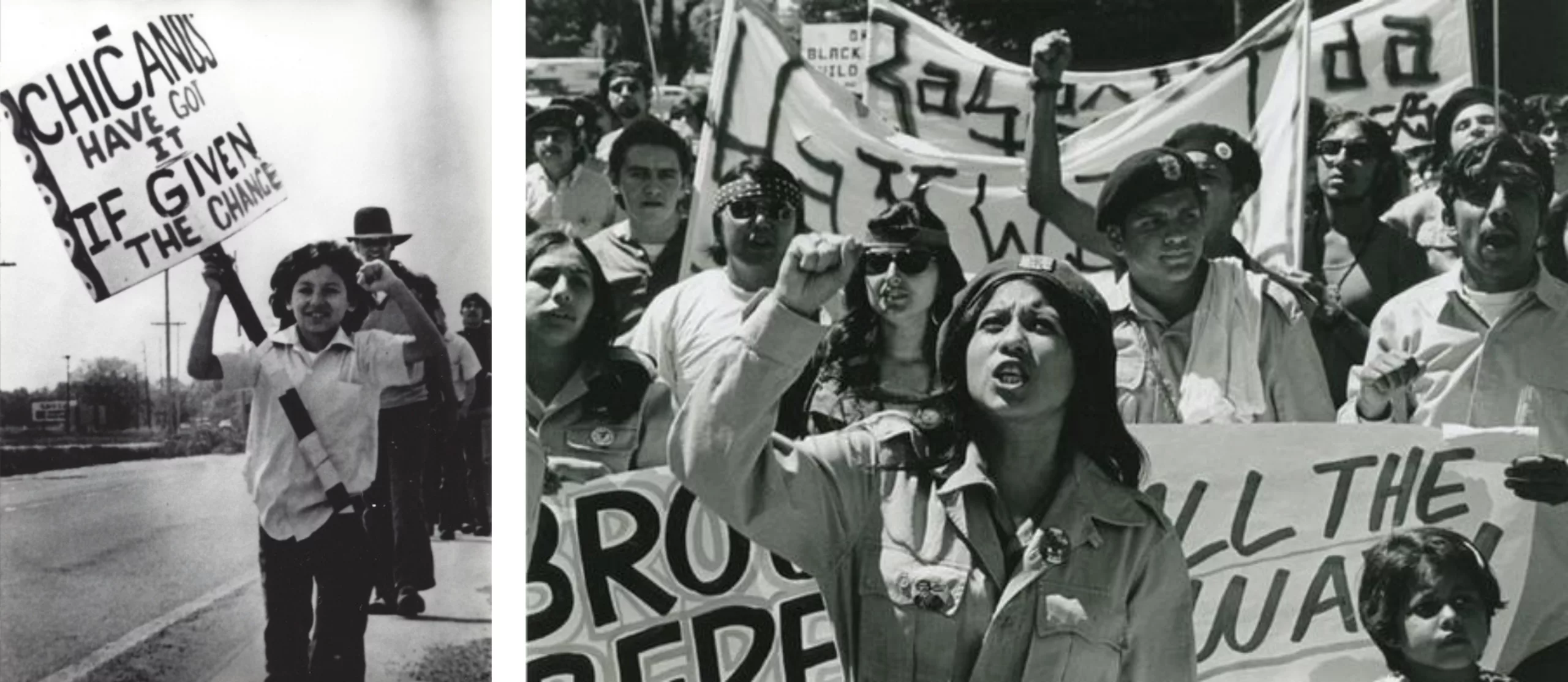

Propelled by African-American emancipation, the raised fist took off and became the gesture of struggle, no longer for workers’ rights, but for civil rights. The descendants of Mexican migrants, the Chicanos, and the indigenous peoples, known as Red Power, asserted their rights to their land by raising their fists. Feminists did the same.

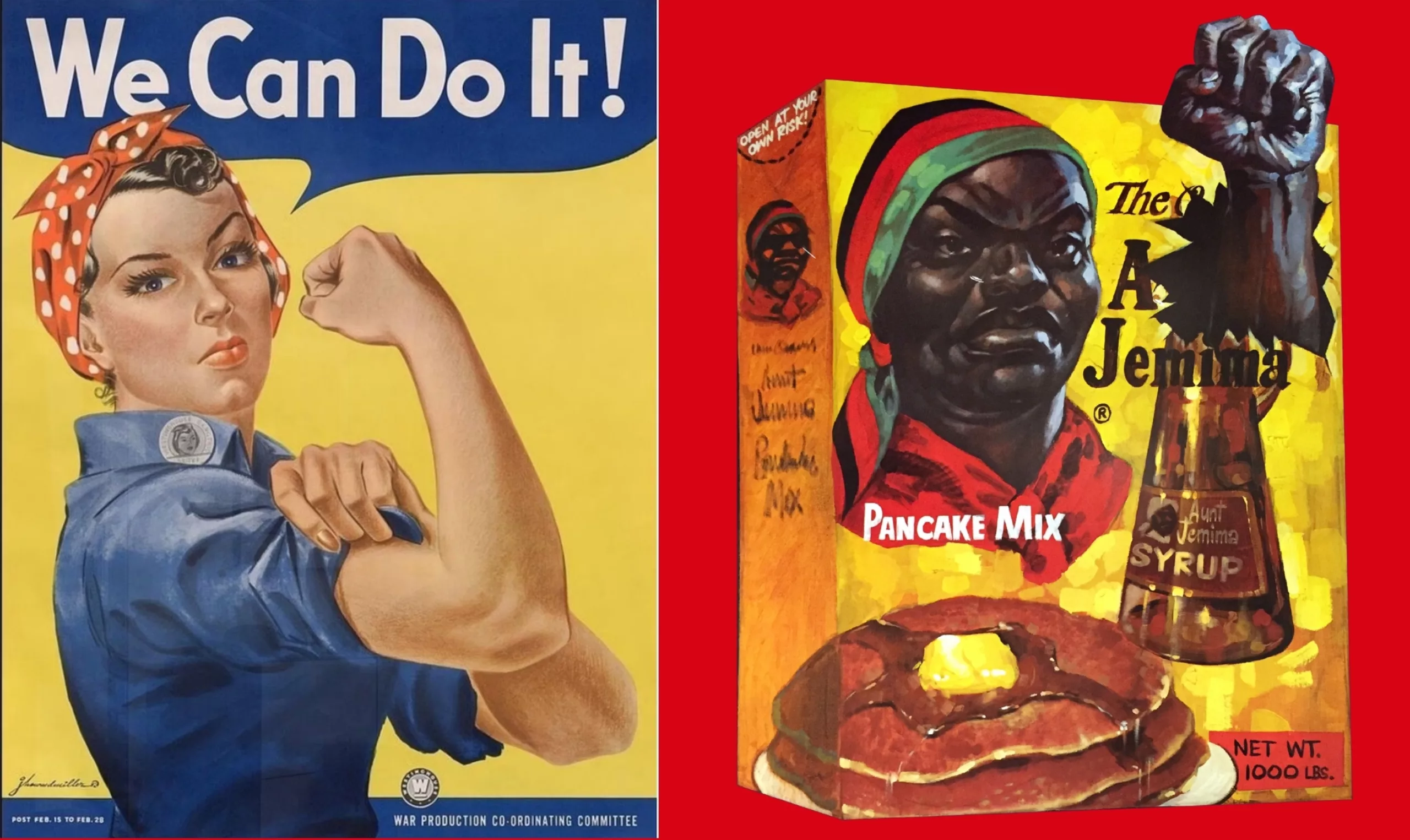

In 1943, J. Howard Miller created the “We can do it” poster, intended to motivate Westinghouse Electric employees to support the war effort. The woman in the poster rolled up her sleeves and raised her fist in a gesture reminiscent of the socialist proletariat of the 1920s.

In 1972, Jon Onye Lockard took the smiling figure of Aunt Jemima and transformed her into a Black Panther activist. (You can read a whole article about racist packaging in our magazine here.)

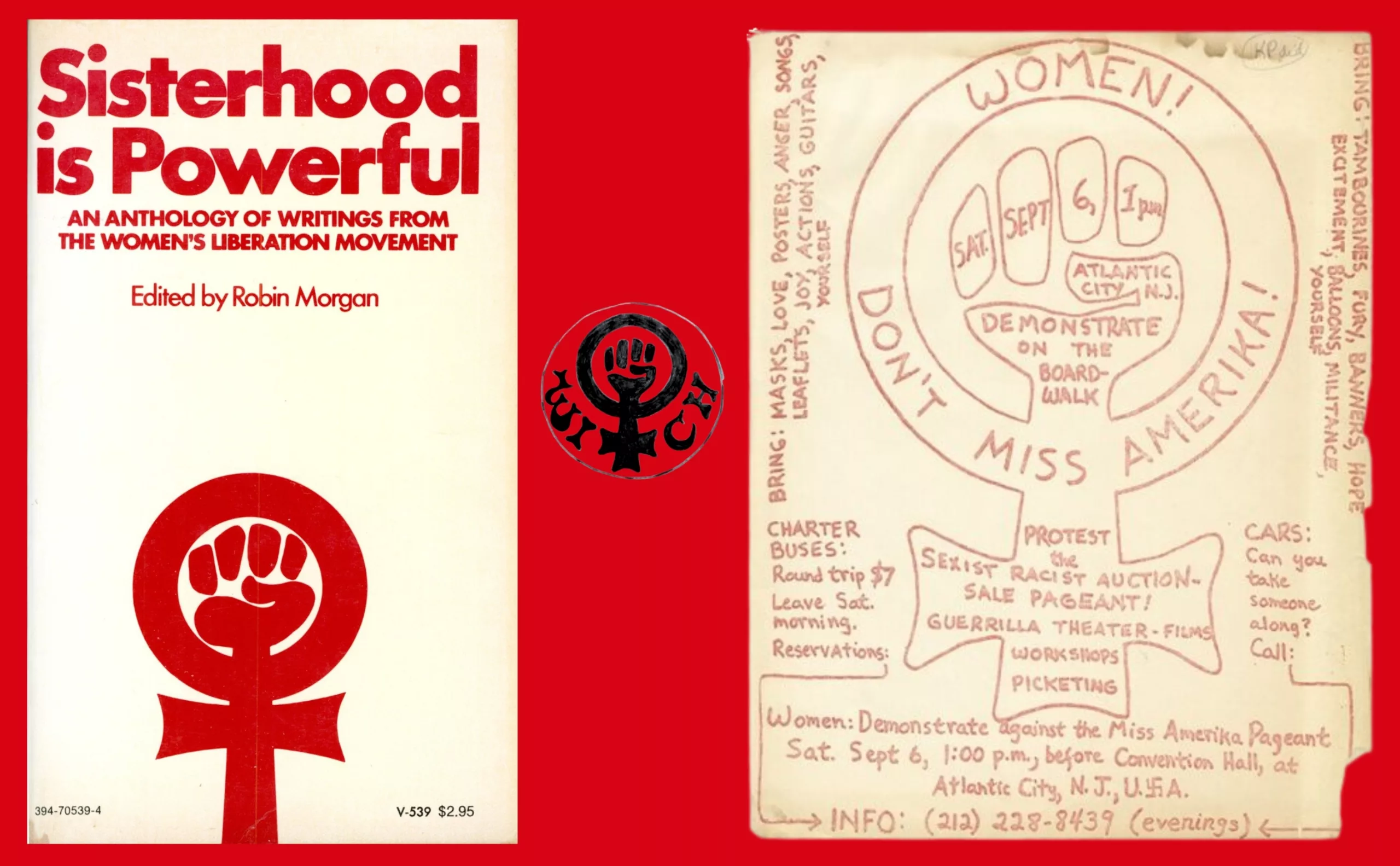

But the feminist movement really gained momentum in 1967 when Robin Morgan, journalist and feminist theorist, drew a raised fist into the symbol of Venus, turning it into the symbol of feminist struggles, “red like menstrual blood” (now used on a purple background, the new feminist color). It was first used by New York Radical Women, one of the first women’s liberation collectives, during a protest against the dictates of Miss America in 1968.

The women crowned a sheep, burned curling irons and bras, and brandished placards to “attack the male chauvinism, commercialization of beauty, racism and oppression of women” symbolized by the beauty pageant. The press focused on the burned bras and the attack on the beauty pageant myth… and new women joined the fight.

Robin Morgan also published Sisterhood is Powerful in 1970, a collection of feminist essays now recognized as one of the most influential books of the 20th century. She helped spread the concept of sisterhood through this book. In 1968, she was a member of the Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell (WITCH), a group of committed feminists who dressed up as witches.

Nowadays, the feminist flag is purple.

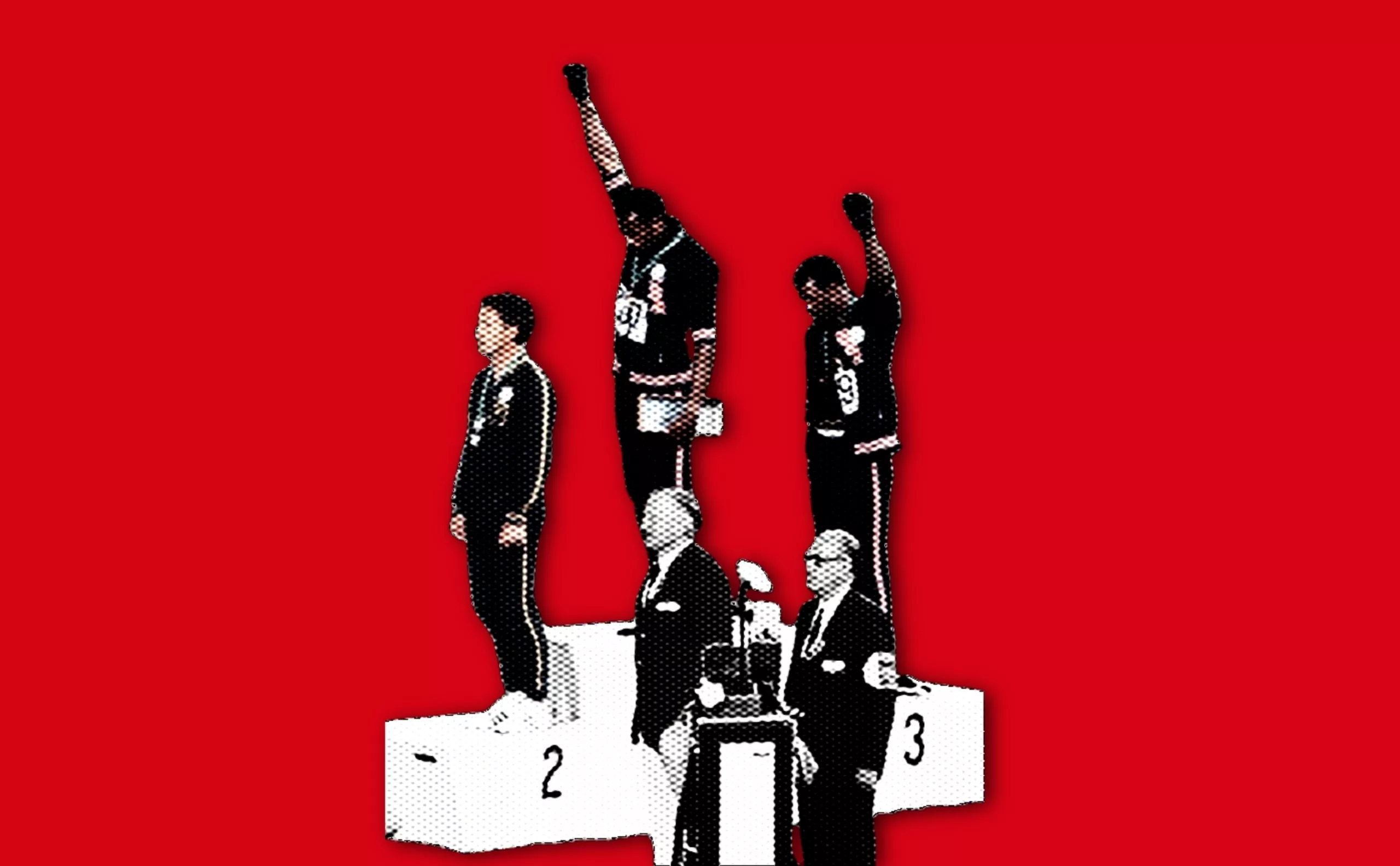

Mexico City 1968: when an athletic gesture becomes a global statement

At the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City, African-American athletes Tommie Smith (gold medalist) and John Carlos (bronze medalist) raised their fists on the podium in one of the most memorable political statements in the history of the Games, watched by 400 million television viewers. They echoed the struggles of Black Power.

Along with Australian Peter Norman, all three wore the Olympic Project for Human Rights badge. Smith and Carlos also adopted other political symbols in support of workers, slaves, and the oppressed black population: black socks, black scarves, pearl necklaces, and open jackets. Tommie Smith clarified, however, that “the salute was not a Black Power salute, but a salute for human rights.” It was yet another sign of struggle, of silent battle.

The price of this political gesture was immediate and brutal. Excluded from the competition and banned for life from the Olympics (since all political gestures are prohibited during the Games), Smith and Carlos received death threats upon their return to the United States, while becoming heroes. Peter Norman was ostracized by the Australian sports authorities and not invited to the 2000 Sydney Olympics despite his exceptional performances.

For millions of oppressed people around the world, this moment definitively transformed the raised fist into an international gesture of protest.

Four years earlier, Nelson Mandela and his fellow prisoners had already raised a chained fist through the bars of the van before their incarceration. Mandela would raise his fist 27 years later upon his release from prison, before becoming the leader we know today.

The struggle and the fist, from Amel Bent to #BLM

For a while, fists were no longer raised. In 2004, however, Amel Bent made it the anthem of an entire generation: “I am mixed race but not a martyr / I move forward with a light heart / But always with my fist raised,” in the legacy of the feminist struggles of the 1960s.

But it was during the Arab Spring in 2011 that it returned to hammer home the struggle and anger against inequality and corruption. That same year, the American social movement Occupy Wall Street challenged the abuses of capitalism and also used this revolutionary gesture.

Three years later, when a young African-American man was murdered by a police officer, three female activists (and Marxists), Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi, revived the raised fist with the #BlackLivesMatter movement, which was propelled by social media. The younger generations have not forgotten the gesture made at the 1968 Olympics. The stylized black fist stencil is a tribute to the Black Panther leather glove, with the symbolic codes of all previous struggles.

Symbolic news among activists and supremacists

The struggle and climate emergency are also evident among activists from Extinction Rebellion and other civil disobedience movements, who do not hesitate to raise their fists… with all the kindness in the world.

Ironically, the gesture has now been adopted by white supremacists and the far right, who use it to embody “white pride,” echoing black pride… Norwegian terrorist Enders Breivik brandished it during his trial to celebrate the murder of 77 people. Trump, meanwhile, shouted “fight!” and “USA! USA!” while raising his fist in an act of defiance after being shot in the ear.

Elon Musk preferred to give the Nazi salute at Trump’s inauguration ceremony, having the “merit” of remaining consistent with his ideas, in line with this fascist tradition. By appropriating the clenched fist, a symbol of social and racial rebellion, supremacists are depriving the oppressed of their signal of struggle and unity.

It’s exactly like when capitalism absorbs anti-capitalist symbols (such as the Peace & Love symbol, the figure of Che Guevara or Frida Kahlo) and turns them into commercial products. It’s as if the fight has changed sides, serving criminals and the privileged, transforming the oppressed into oppressors.

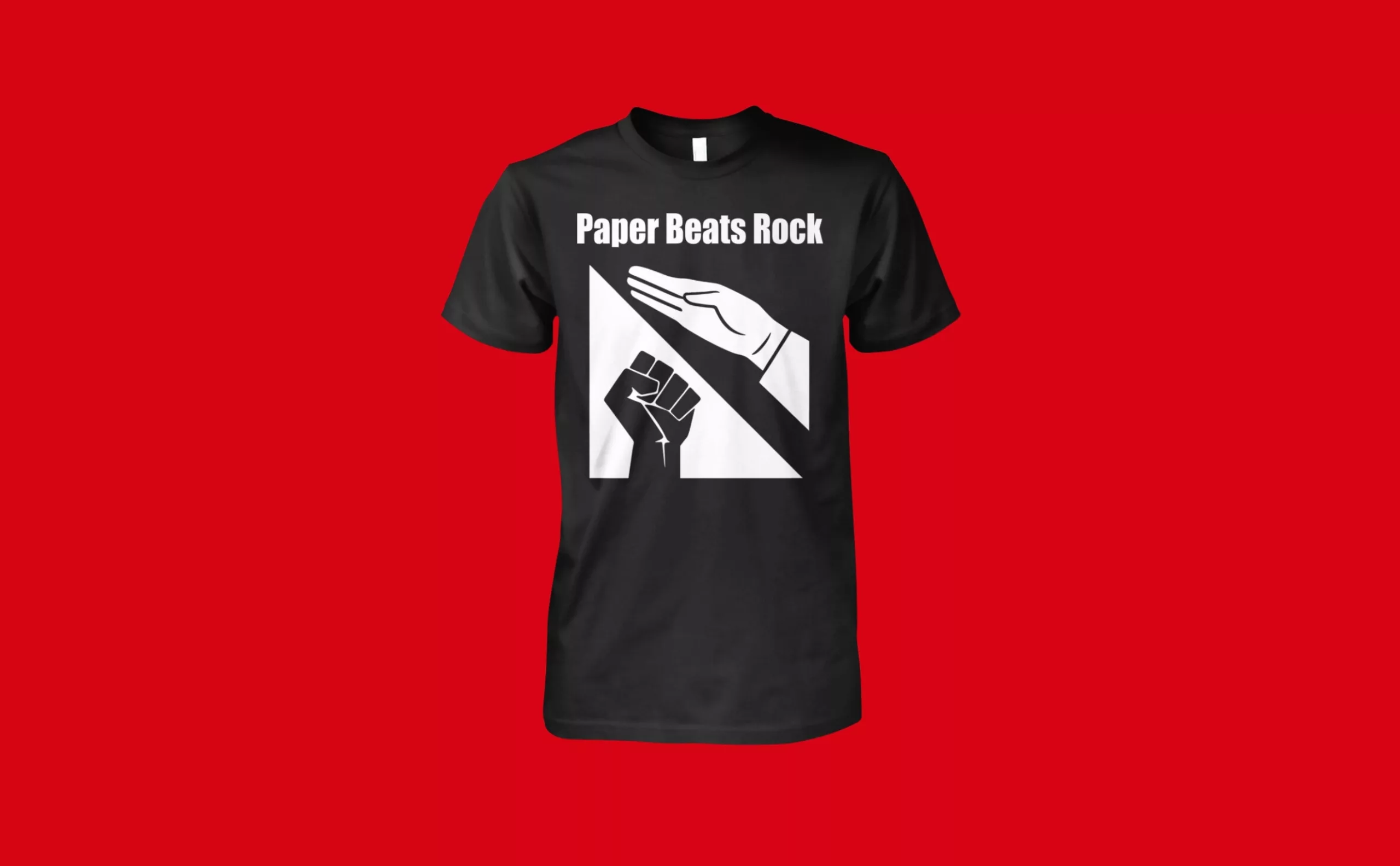

Walmart recently caused a scandal by selling a “paper beats rock” T-shirt featuring two hands that were not exactly innocent… It was quickly withdrawn from the market.

But true anger, a century-old legacy, and the desire for equality cannot be erased from memory. The raised fist will always rise up.

PS: By coincidence, this article is published on November 25, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. Wethus end this article with photos of demonstrations taken by Instants Subtils Photographie, and fists raised by and for women.

Sources :

arte — Black Lives Matter. Un symbole, une cause

Vergnon, G. — Le poing levé, du rite soldatique au rite de masse.

MoMA – Ten Minutes with Emory Douglas: On Arts Activism.

SFMOMA — Emory Douglas: REPARATIONS.

Konbini — Poing levé, tête baissée, black power : l’histoire de cette mythique photo qui a marqué les JO de 1968.

Yakaranda — L’histoire derrière le poing serré-et comment il est devenu le symbole du Black Power.

Ory, P. — L’histoire des politiques symboliques modernes : un questionnement.

OpenEdition Journals. — Du Black Power au mouvement Black Lives Matter.

SF Gate — Artist Frank Cieciorka dies in Humboldt County.