What strategies are hidden behind the mascots’ smile?

This article is the third in a series about mascots, from their historical origins to their digital transformation. Find all the articles here:

- A history of mascots

- Brand mascots, from Bibendum to Bunny the Bull

- What strategies are hidden behind the mascots’ smile?

- Mascots and virtual avatars in the digital age

As we saw in the previous article, the shape of mascots has a crucial impact on how customers perceive the brand, in addition to their “personality.” But what powerful strategies also lie behind their benevolent smiles?

Humanizing brands with “living” mascots

Often bipedal or at least standing upright, endowed with their own personality, and ultimately humanoid, mascots allow us to project human feelings onto imaginary beings (even Kan-Chan, the enema pear-shaped mascot in Japan). These friendly and likable spokescharacters, because they “resemble” us, help make brands more memorable. In the case of the enema pear, the cute pink design makes the product more playful and therefore less daunting to use, especially for children. The mascot transforms an unglamorous medical object into a fun little game. Or at least, it tries to.

A study conducted by Opinion Way in 2013 found that a mascot increases consumer engagement with a brand by nearly 43%, with an even higher rate in the service sector, where it creates a reassuring and tangible image.

Jean-Claude Boulay, a semiologist, explains that “the direct benefits of using a mascot are visibility, simplicity, immediacy, and memorability. A mascot allows emotions to be conveyed through personification and induces trust by creating a bond and complicity. The mascot serves as a kind of emanation; it is a spokesperson for the brand.” Creating cute characters in our image to sell better works, and it’s probably the idea of the century.

But can a mascot be used at any cost, and especially to promote just any product or service? Isn’t there a hidden flaw in trying to make everything cute, even products that don’t benefit those who use them? Concretely, how can such a simple idea work so effectively? Why are we so attached to mascots?

Increasing brand recognition, especially among children

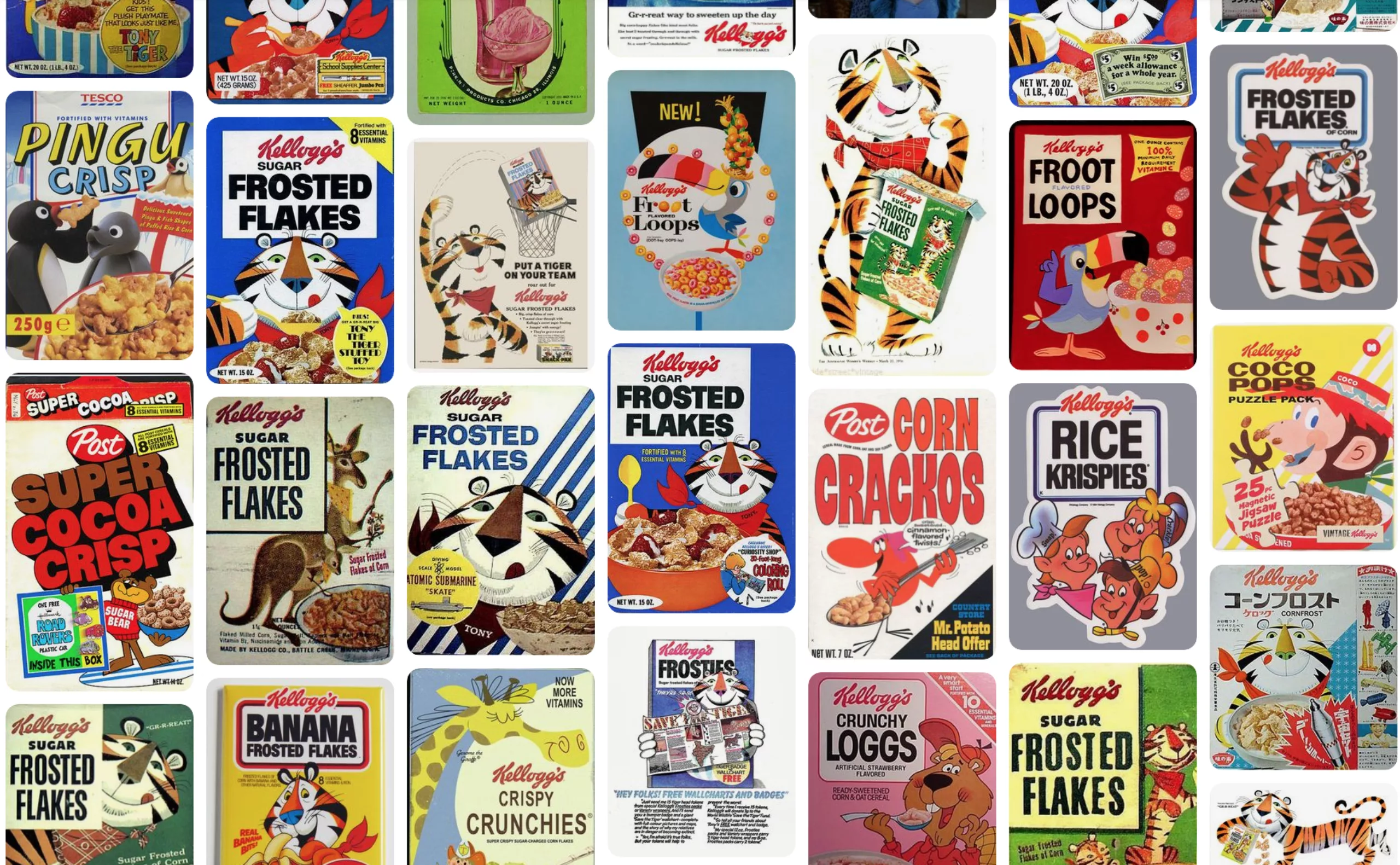

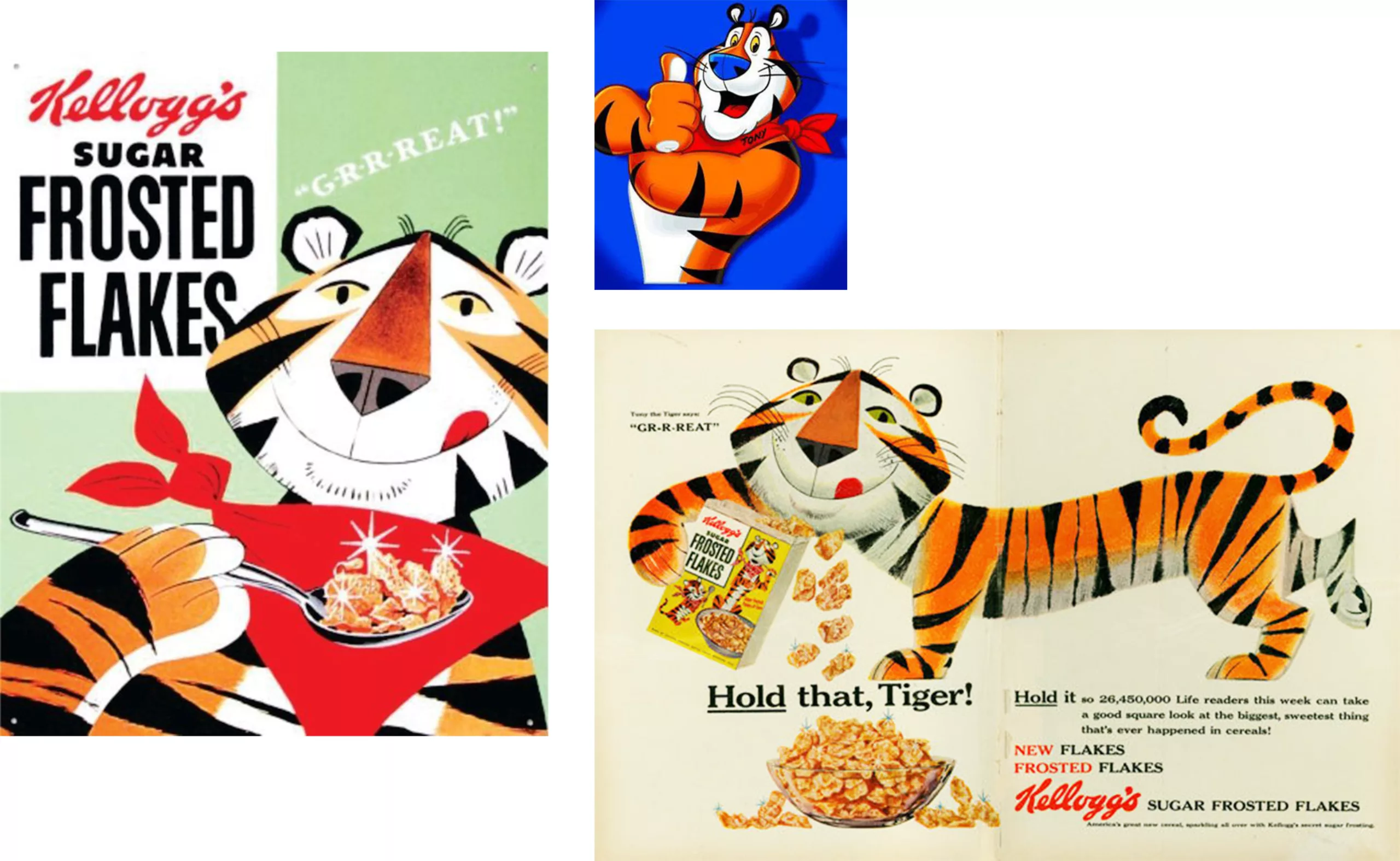

First, because we see our first mascots during childhood, at an age when everything is an excuse for attachment and empathy. From the tiger to the kangaroo, passing through the rabbit and the toucan, nearly all children’s cereals have their mascot, which then plays the role of an ideogram, a drawn idea that doesn’t require the ability to read. This mascot conveys a universally friendly language that says, “Look how cute I am,” attracting the child just like a cartoon character would.

Before learning to read and depending on their language skills, a child does not distinguish between the real world and a fictional or imaginary universe. Their world is filled with real beings or false beliefs and fictional characters are part of their reality. The presence of a tiger on a cereal box reinforces the idea of a friendly being or even a friend for life just like a comfort toy or another child and thus ensures better visibility and immediate recognition among children while increasing trust in the brand. The child grows up with this ever-present image and keeps it in their heart as they mature. From a marketing strategy perspective, this is incredibly effective.

The mascot then replaces the logo or written sign and allows for better, more lasting memorization with this target audience, especially among children who cannot read.

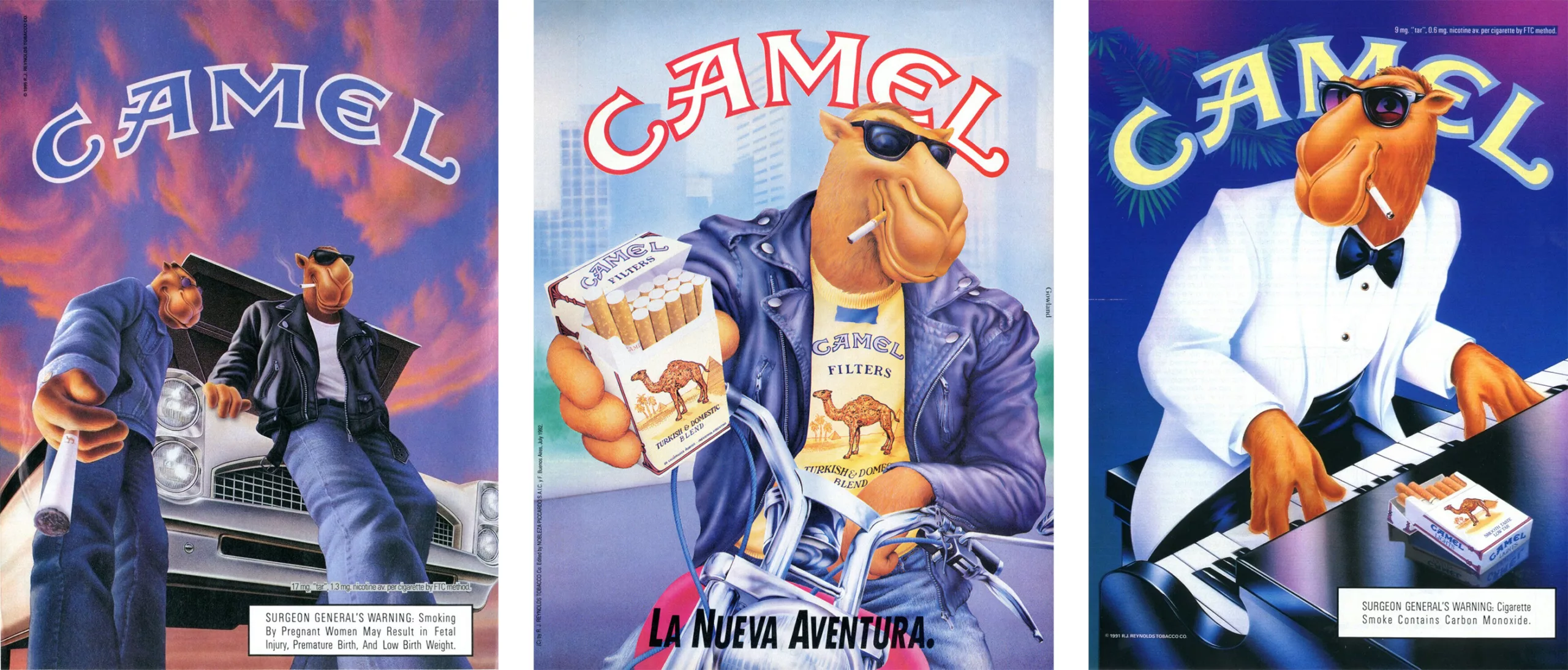

Mascots that cause controversy

In hindsight, isn’t this a really unhealthy strategy to try to turn a child into an indirect consumer so early on (since they are not the ones buying), especially when it comes to promoting products harmful to their health? Think of heroes like Malabar, the Pringles mascot, the Haribo bear and child, or even Kinder Surprise toys which, although not mascots per se, triggered a dopamine rush at the sight of the chocolate egg. Worse still, some brands create derivative products from children’s favorite cartoons like Peppa Pig or Dora, which are real sugar bombs and exploit children’s emotional attachment. A UK study showed that 51% of packaging featuring friendly mascots or cartoon heroes aimed at children promote products high in sugar and fat, compared to only 3% for healthy products (source: The Guardian).

In 2018 in England, members of the Health and Social Care Committee called for banning mascots, cartoons, and junk food advertisements on television to combat childhood obesity (source: Sky News), describing these practices as “irresponsible and disgusting.” Meanwhile, Mexico passed a law prohibiting the sale of sugary and fatty products to minors, treating them like alcohol and cigarettes, in a country where 73% of the population is overweight (source: The Washington Post). Mexico also introduced specific black warning labels on packaging for products high in sugar or fat. “What was true for tobacco can also be true for refined sugar, which is just as deadly.” And addictive.

Finally, since we’re talking about mascots that cause controversy, we invite you to (re)discover our article on racist packaging, where we addressed the legacy of brands like Uncle Ben’s, Aunt Jemima, and Banania. We also think of mascots for toxic products, such as those on cigarette packs, which had their moment of glory before being banned.

Mascots and Their Impact on Our Brains

But let’s get back to our mascots, this time for adults. It is interesting to highlight just how much a mascot plays on the emotions of potential customers, and if this strategy works, it is no accident. Mascots tap into our childhood memories. Again, the idea is not to glorify this strategy but rather to understand its underlying mechanisms, perhaps to help us take a step back when needed, or to encourage brands to reflect before creating a mascot.

A bit like robots, puppets, or comfort toys, they help tell stories by extending the brand’s storytelling, halfway between emotions and a return to childhood. Humanoid mascots amplify this feeling of trust and empathy by weaving a positive emotional bond: the kawaii effect, the cuteness of “plush” mascots and their presence everywhere in public spaces make them attractive and effective. For example, in Japan, they allow people to revisit their childhood and escape the pressures of adult social norms. Elsewhere, mascots evoke pleasant feelings in those who see them; this is what neuroscience explains in more detail.

Mascots as Antidepressants?

In our brains, there are mirror neurons: by looking at someone else, we see ourselves as if in a mirror and “activate” our own motor neurons, even without making any movement. This reflex increases our natural ability to “feel from within” others and to put ourselves in their place, through empathy. Thanks to these mirror neurons, our brain releases endorphins when seeing a person (or a mascot) who appears happy: we smile at them, or imagine smiling ourselves, by mimicry. Charles Darwin explained that “even the simulation of an emotion tends to produce it in our brains,” meaning that we are capable, through mental imagery, of experiencing emotions (or movements) just by imagining them. Anthropomorphic mascots who smile at us therefore help us feel better. Investigator Ron Gutman even stated that “a smile can generate the same level of brain stimulation as 2,000 chocolate bars.”

Making us smile to help us remember

Another advantage provided by a smile is that our brain gets more oxygen and better retains the information it receives, thanks to the activation of the limbic system, also called the emotional system. In other words, a message gets across more effectively when it makes someone smile or laugh. So a smiling mascot or one that makes people smile, combined with a humorous advertisement = a message doubly better retained. A smiling mascot can therefore have a real impact on our brain by both fostering empathy and helping us better retain a message, especially if it is humorous.

Mascots also remind us of a reassuring childhood figure, which rekindles the memory of attachment to others.

Are mascots our parents?

Indeed, the surreal proportions of mascots, their soft fur and round belly, their comical gait, and their large eyes with a smiling mouth also make them a kind of giant stuffed toy. Much like a comfort blanket, they create a reassuring attachment to the brand, turning it into a substitute figure. We have seen this with the Cetelem character, whose soothing curves reassure and inspire confidence, but also with Japanese mascots, which are soft as well as smiling, inviting both adults and children to cuddle them.

And if mascots trigger a “comfort toy effect,” it may be because their physical features emphasize two large round eyes and a curved or triangular mouth, which might resemble what we perceived of our parents from birth. Infants, whose vision is 10 to 30 times less developed than that of adults, primarily perceive simple and full shapes like triangles, squares, and circles rather than details, as well as bright, contrasting colors (source: unige.ch). One can then imagine that a parent’s face looks roughly like a mascot to a newborn! Upon closer inspection, the combination of two ovals plus a triangle is found in almost all mascot faces.

As Joffrey Becker says in The Human Body and Its Doubles, “the empathy that humans feel arises from the recollection of a lived experience.” So mascots would remind us of the smiling faces of our loved ones? No wonder we get attached to them.

Play, to remember better

Finally, as André Stern explains in his book *Jouer, faisons confiance à nos enfants* (Actes Sud), “neurobiology now proves that no lasting learning is possible if our emotional centers are not activated.” Enthusiasm is what activates these emotions and stimulates the brain, notably through play or humor, as we saw earlier with the effects of smiling. For children and even adults, play is the foundation for cognitive development. Thanks to a mascot and the enthusiasm it generates when well done, a brand can invite spectators to take it beyond the realm of the brand and integrate it into their private lives. For example, mascot-related products like comics, cartoons, or figurines allow people to appropriate the mascot as a tool for play or entertainment. This was the case with the Bibendum albums, Malabar tattoos, or the figurines found in cereal boxes.

But it seems the era of big, cuddly mascots is over. While they are still used in communication campaigns, today’s new mascots look more like virtual avatars than plush toys. In our next article, we will explore modern mascots in the digital age.